Trustee Emerita Mimi Gardner Gates talks to Scholar Julien Domercq about all things history of art.

When Bill Gates Sr discussed the grant that would establish the Gates Cambridge Trust 25 years ago it was always with the widest possible lens on how scholarship can make a positive difference in the world.

“When Big Bill and Bill and Melinda envisaged the scholarship they saw it as being open and broad, for bright young minds from all areas who are full of idea and energy and are ready to go out into the world and help others,” says Trustee Emerita and Bill Gates Sr’s wife Mimi Gardner Gates.

She was speaking to Gates Cambridge Scholar Julien Domercq [2013]. Julien’s PhD focused on the shift in depictions of the peoples of the Pacific in British and French art from idealisation to demonisation between the Enlightenment and the Age of Empire. At the time he did it he was struggling to think how the history of art could contribute to the Gates Cambridge mission of improving the lives of others. “I wasn’t curing diseases,” he says. Mimi laughs: “You were curating them!”

She is clear about how art can help others. A distinguished museum curator and then director, she says: “Museums change lives every day by provoking people to think. Museums don’t just exhibit beauty; they change people’s perspectives on the world. They improve lives constantly. Works of art express the values of humanity and who we are and the wonderful diversity throughout the world.”

Julien agrees, but says he found working on art in an academic setting meant he missed out on the wonder of being in close proximity to art works. “I wanted to reach out to a bigger audience and facilitate interactions between people and works of art,” he says.

Even during his PhD, he was working at the National Gallery. There he curated exhibitions on everything from Degas to Post Impressionism. Now a curator at the Royal Academy of Arts, he agrees that art “improves lives quietly” and he is keen to make the deep relationship between viewer and artwork more accessible to everyone.

Covid, of course, took that in-person experience away from people. Everyone went online, but Julien says people still sometimes think they are not seeing the real thing when they go to an exhibition. “I listen to the comments at the visitors’ desk and they think the real thing must be locked away in a safe,” he says. “It highlights the work we need to do to remind people that museums are extraordinary democratising places where they can commune with works of art and deeply experience the real thing, which is even more important in an age of screens and consuming images.”

Mimi adds: “The best way for a drawing to persist is to lock it away, but does a work of art still exist if no-one can see it? Finding a balance between a work’s conservation and accessibility is one of the most fascinating aspects of curation. Museums both preserve and share.”

Mimi’s career

Mimi’s career began with a degree in art history at Stanford, where, inspired by a professor, she embraced Asian art and embarked on an exchange to Japan. After graduating from Stanford, she spent two years at the École des Langues Vivantes in Paris studying Chinese language and culture. The following year, she and her husband drove in a Land Rover from Paris to India where they spent three months studying Indian temple architecture and sculpture as well as other magnificent monuments. The pair returned to the US and Mimi, who had studied Chinese, began a master’s in Asian Studies at the University of Iowa followed by a PhD in Art History at Yale.

Once her Yale doctorate was completed, she started working at the Yale University Art Gallery as assistant curator in the Asian art department. Just five days into her role, the senior curator of Asian art abruptly departed. “Suddenly there I was,” says Mimi. “It was wonderful because the director let me fly.” Over the next 12 years while doing research and teaching the history of Chinese art at Yale, Mimi curated many exhibitions before being appointed director of the museum, a post she held for seven years. Through the 1970s female directors of art museums were few; only one woman director per decade was admitted into the Association of Art Museum Directors. “Being director of the Yale Art Gallery was one of the greatest art jobs in the world,” says Mimi.

Julien notes that while there seemed to be an element of serendipity in Mimi’s career, she had to be ready to seize the moment when she was offered her first curation job. “I did not think twice,” agrees Mimi, “even before I had thought about what a career in museums would mean. I was able to teach, research and curate exhibitions. I feel blessed in my career.” In 1994 she moved from New Haven, Connecticut (Yale) to Seattle, Washington, to direct the Seattle Art Museum, a post she held until 2009 when she retired and founded the Gardner Center for Asian Art and Ideas, an integral part of the Seattle Art Museum. Now Mimi is Director Emerita of the Seattle Art Museum.

Mimi’s first exhibition was on the ideal of feminine beauty in the Japanese print. Highlights over the years have included the Traces of the Brush, a major exhibition at Yale about Chinese calligraphy in 1977 and a 2016 exhibition at The Getty Center in Los Angeles entitled Cave Temples of Dunhuang: Buddhist Art on China’s Silk Road, which featured three full-size hand-painted replicas of caves from Dunhuang, China, housed inside a structure that was specially built for it. The Getty Center usually does not exhibit copies of artworks, but the caves, a UNESCO World Heritage site, could clearly not be moved. In addition, for the exhibition the Getty borrowed more than 40 rare manuscripts and works of art from London and Paris that had originally been in the caves. Over 200,000 people visited the exhibition which offered a unique way for them to experience the art and architecture of the ancient Buddhist cave temples.

Mimi, who has her own personal collection of Chinese art, says her greatest professional acquisition is an Olympic sculpture park one mile north of the Seattle Art Museum. The park is free and open to everyone and is, says Mimi, a work of art in itself. “A collector came to me and said Seattle needs a sculpture park so I said let’s do it,” she says. “I always dreamed of getting art outside museum walls.”

Julien’s work

Julien is also very interested in experimenting with ways to enable the public to engage with art in different ways. His Degas exhibition in 2017/18, for instance, was the most visited exhibition at the National Gallery, attracting around 400,000 people. The show consisted of around 30 works shown in three different themed spaces. The works were on paper so they were fragile and required low light levels. Julien wanted to make a virtue of that and build an ambience, to make them shine like jewels and to create an atmosphere. It worked and people found a way to commune with the works.

Julien was keen to ask Mimi about practical issues such as de-accession – when artworks are removed through an agreed method – budgetary pressures and some of the ethical issues facing museum directors, for instance, Mimi’s role in the restitution of Matisse’s Odalisque after it was discovered in 1999 to have been looted by the Nazis. Mimi said there was a lot of media attention at the time and pressure to respond quickly, but that, given paintings at the museum are held in public trust, the museum needed to research its provenance. In the days when the painting was donated people didn’t ask as many questions as they do now about provenance. “No-one wants a stolen object, but often we just don’t have the information,” she says.

Julien was keen to ask Mimi about practical issues such as de-accession – when artworks are removed through an agreed method – budgetary pressures and some of the ethical issues facing museum directors, for instance, Mimi’s role in the restitution of Matisse’s Odalisque after it was discovered in 1999 to have been looted by the Nazis. Mimi said there was a lot of media attention at the time and pressure to respond quickly, but that, given paintings at the museum are held in public trust, the museum needed to research its provenance. In the days when the painting was donated people didn’t ask as many questions as they do now about provenance. “No-one wants a stolen object, but often we just don’t have the information,” she says.

Mimi’s keen interest in art, especially Asian art, continues and she loves discovering new artists. She travels a lot in Japan and China. Mimi, who has been on the board of numerous arts organisations, came to the UK for the celebration of the 25th anniversary of Gates Cambridge in May and last year was at the opening of Bill Gates Sr House. She feels Bill Sr would be very proud of everything Cambridge has achieved in terms of the Gates Cambridge Scholars and how they have diversified the university. “The opening of Bill Gates Sr House was something he would have revelled in,” she says. “He felt very strongly that all the Gates Cambridge Scholars deserve the very best place to work and gather. He would have been so honoured to have a building named after him.”

Julien says the building embodies the sense that the Scholars have been very lucky and that it is time to redistribute that luck. “It’s a multiplier,” he says. Mimi echoes his sentiments, saying the family motto is to those whom much has been given, much is required. Both are looking forward to what the next 25 years of the Scholarship will bring.

*An edited version of this interview appears in the Gates Cambridge 25th anniversary magazine, which is just out here.

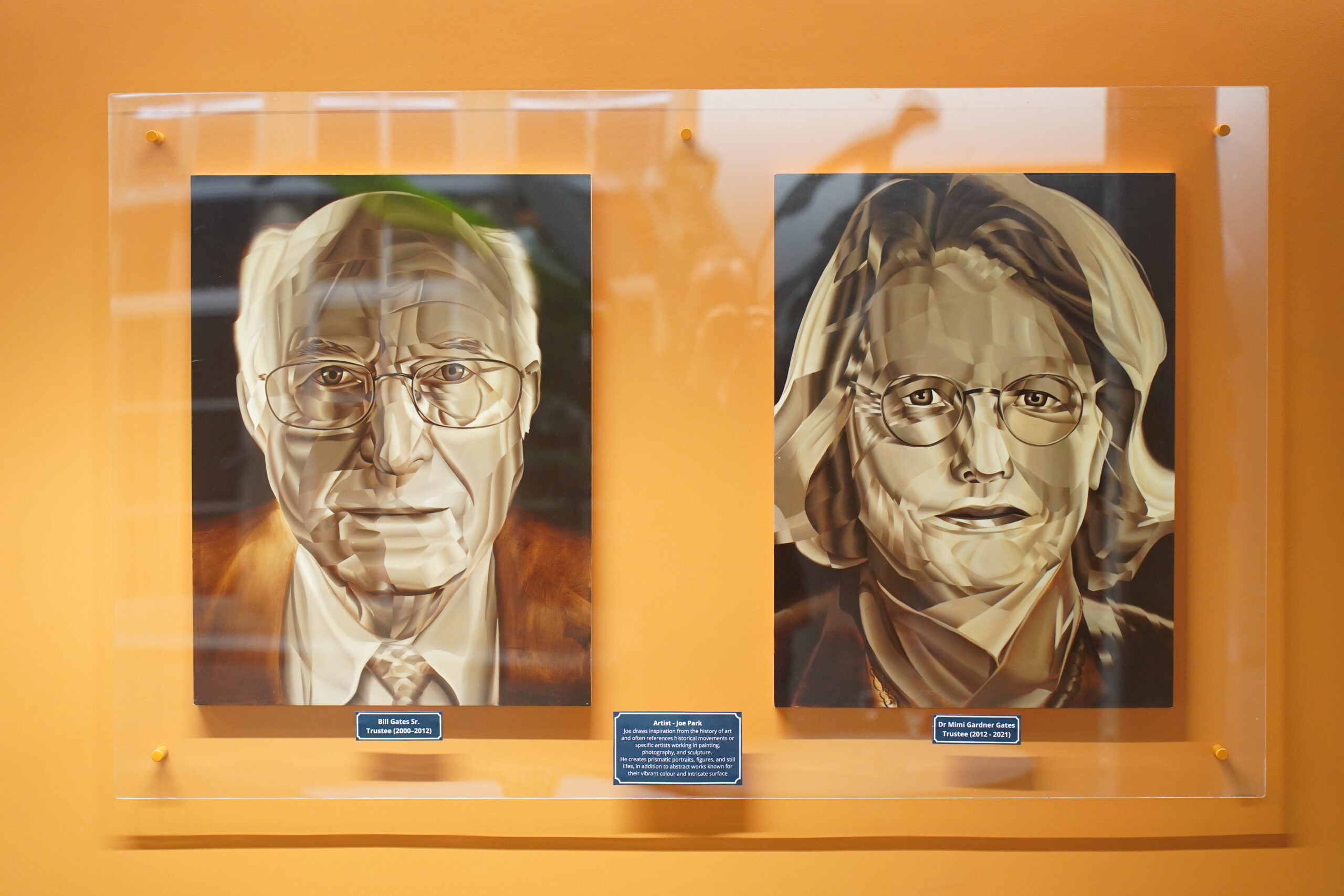

**Top photo is of the new portraits of Mimi Gardner Gates and Bill Gates Sr by Joe Park on display in Bill Gates Sr. House.