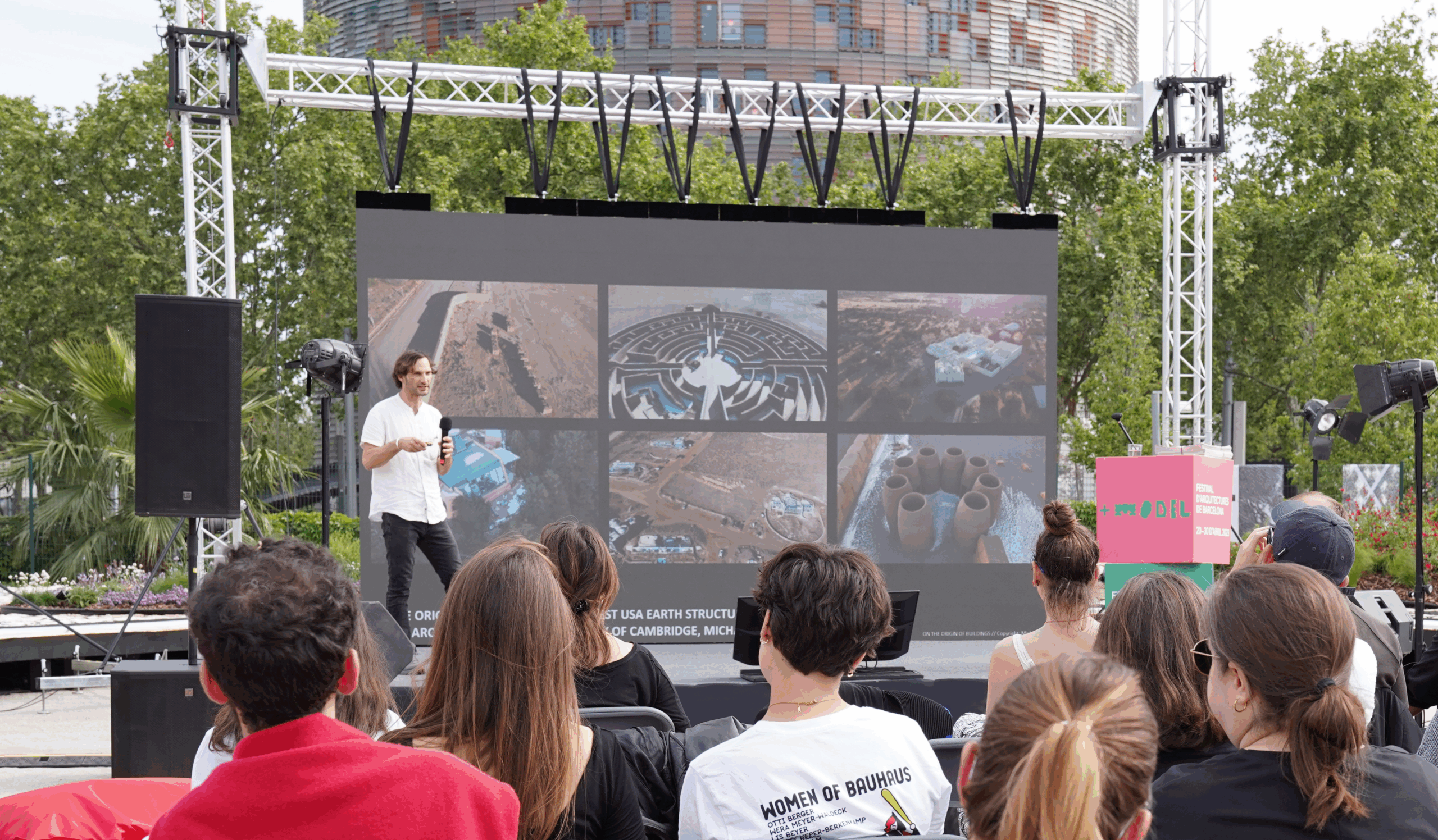

Michael Salka talks about his research into how bio-based building materials can be normalised and standardised so they get more traction.

In every place there are historical traditions when it comes to materials used for building and wisdom about the application of these materials and how they respond to the local climate.

Michael Salka

Michael Salka is interested in pushing the boundaries of architecture, but also in learning from past knowledge about bio-based building materials and how they adapt to different conditions.

He began his PhD in Architecture in 2021 on bio-based solutions to the future of building. It investigates how geospatial networks can inform place-based natural material value chains to meet worldwide demand for housing while mitigating and adapting to global climate change by advancing carbon neutrality and resource security and addressing ecological concerns as well as promoting human health and wellbeing.

He is looking in particular at how bio-based building methods, specifically engineered timber made of multiple layers of wood and other related natural products, can be normalised and standardised so they can gain more traction. Bio-based materials, including wood, account for just 3% of the mass of building material used in Europe.

Michael [2021] is comparing what is happening in places where innovation is occurring, including Indonesia’s bamboo villages and Norway’s tall engineered wood buildings. “I am not studying how the the buildings themselves work, so much as how they arise from traditions and resources coming together to create a throughline from historical material use to emergent bio-based material use,” he says.

“In every place there are historical traditions when it comes to materials used for building and wisdom about the application of these materials and how they respond to the local climate. We don’t always connect that historical knowledge with what is happening in contemporary times so that those ideas can evolve and be implemented in different circumstances – or in different places.”

Childhood and undergraduate studies

Michael was born in Philadelphia where his father was studying to be a doctor. Soon after he got a residency in New Mexico, then the family moved to the small mountain town of Durango, Colorado. Michael spent his childhood outdoors, building forts with other children and playing. “Looking back, that was pretty foundational,” he says. At the time he felt confined by living in a small town as he was interested in the arts and culture associated with bigger cities. With time he has come to appreciate that the intimacy with nature he experienced was fundamental and says that it has formed a cornerstone of his current work.

Michael’s mother was a nurse and his two younger sisters work as a school teacher and baker respectively. Both his parents had a strong work ethic and a belief in helping people. They were also keen that Michael was exposed to people from a wide range of backgrounds and cultures. Michael attended his local public school in Durango. While he was good at sciences and mathematics, he was more drawn to the arts. He was also in a number of experimental bands at school.

When he applied to the University of Colorado Boulder in 2009 he was initially focused on film studies, but he became more and more interested in climate change. Architecture combined his skills in mathematics and his interest in the arts and was an avenue for him to promote ecological approaches to building. So soon after he started his degree, he switched from film to environmental design. Alongside his studies, Michael held three jobs – as a graphic designer on a sustainable transportation programme, repairing abandoned bikes for donation and discounted resale, and as a structural engineering tutor for architecture students. He also spent two summers working on infrastructural development and water management in Rwanda with Engineers without Borders.

When he applied to the University of Colorado Boulder in 2009 he was initially focused on film studies, but he became more and more interested in climate change. Architecture combined his skills in mathematics and his interest in the arts and was an avenue for him to promote ecological approaches to building. So soon after he started his degree, he switched from film to environmental design. Alongside his studies, Michael held three jobs – as a graphic designer on a sustainable transportation programme, repairing abandoned bikes for donation and discounted resale, and as a structural engineering tutor for architecture students. He also spent two summers working on infrastructural development and water management in Rwanda with Engineers without Borders.

After graduating, Michael interned with a professor at his school who was working on the largest net zero master plan in the US. “It helped me understand environmental buildings, but I felt there was something lacking on the architecture side,” he says. Michael wanted to explore the world and see it from different perspectives so he and his girlfriend [now his wife] travelled across Europe for a year. The experience greatly expanded Michael’s architecture vocabulary. He was inspired by the vibrancy of public spaces which changed his priorities when it came to design. “I became more interested in the relationship between nature, culture and place and how that had grown up over time,” he says.

After a year on the road, however, Michael and his girlfriend were exhausted and out of money, so they returned to the US. Michael got a job at a relatively small architecture firm in Denver which was doing innovative work on reusing space. For instance, they turned their office into a gallery for a local arts festival and invited artists to exhibit there. Michael stayed at the firm for two and a half years and learned a lot about leadership and different roles within architecture. He realised, however, that he needed to expand his computational design skills so he could communicate better the value of environmental issues. “I had gained an understanding of how the industry worked, but I wanted to push it forward,” he says.

Postgraduate studies

He opted to do a master’s at the Institute for Advanced Architecture of Catalonia in Barcelona in 2018. He was interested in their flagship programme on integrating technology into architecture, but was persuaded to join a new programme on ecological buildings and biocities. The course was taught in English to a group of 19 students from 14 different countries and involved experiential learning. The students lived and worked at the Institute’s Fab Lab based in a natural park, a green island in the urban environment of Barcelona and surroundings.

“Even though the campus is quite near Barcelona’s urban core, it feels like a rural forest,” says Michael. “The Fab Lab is in a farmhouse that has been retrofitted to enable students to do digital fabrications and prototyping, with the forest landscape being used as part of the laboratory’s facilities.” The wood from the trees grown in the forest isn’t of a type usually suitable for architecture, but by combining multiple small pieces in engineered compound assemblies the students can use it to build with. The wood is layered with other natural materials, keeping the entire system low carbon and allowing the buildings to breathe and stay cool while also making them slower to burn. This has positive health outcomes on their occupants. It also has positive outcomes on the health of the forest, because the trees are carefully and individually selected before harvesting, based on their role in the greater ecosystem.

After completing his one-year master’s course, Michael did some teaching work at the Institute while he built his research and development portfolio. He was in Barcelona for the pandemic and saw how the city was able to manage a strict lockdown while maintaining a strong community spirit. The Fab Lab also became involved in 3D printing ventilator valves and masks for aid workers. And it won a grant to produce urban furniture made from local wood to improve the pedestrian environment, boost street safety and enable socialising outdoors without risking contagion.

Since then Michael has stayed in touch with the Institute, is still involved in both teaching and research projects and has collaborated with them for his PhD on more innovative approaches to building with engineered timber.

He was recently awarded the Gold Prize in Architectural Design from the prestigious Design Educates Awards 2025 for his co-direction of a project there entitled CORA (the Cathedral of Robotic Artisans). CORA involved repairing and retrofitting an historic brick stable by removing the dilapidated roof and sensitively inserting an arborescent timber structure, manufactured with digital tools, to shelter a new six-axis robotic arm workshop.

At Cambridge he has also been involved in the Gates Cambridge community on the Scholars Council. He says it gives him more international perspectives as well as ideas from different disciplines. “It has been very valuable and the friendships I have made have helped shape my thinking,“ he says.