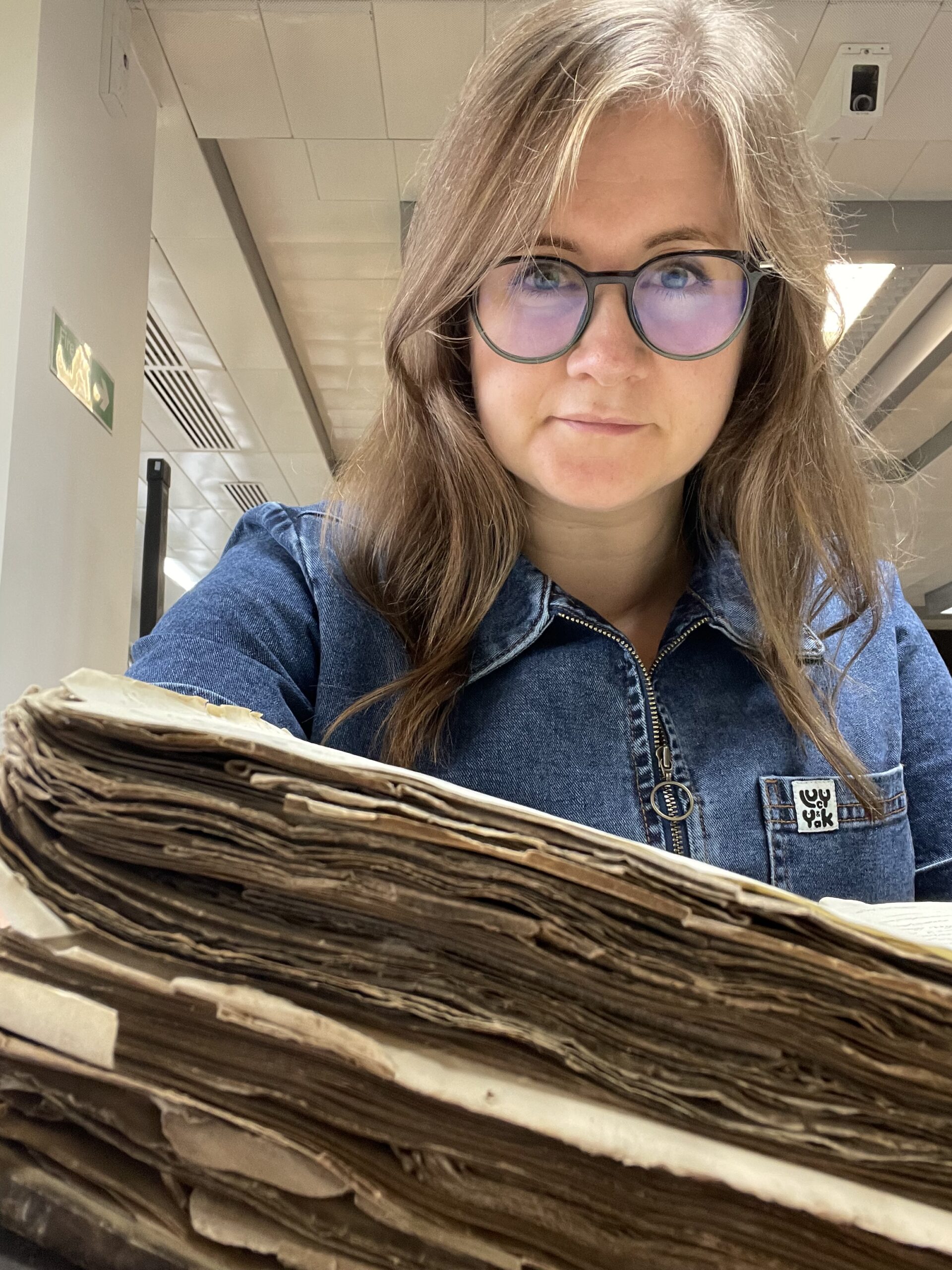

Shealynn Hendry's research looks at how we understand the history of displaced people with complex legal identities and ensure they don't remain silent in the historical archives

I was fascinated by the long-term effects of displacement and the people who are antithetical to national binaries. Where do you find them in the records? What identity do they have?

Shealynn Hendry

How do we ensure that the lives of displaced people and those with a complicated legal status are documented in national archives? Before she started her PhD, Shealynn Hendry [2022] worked in refugee camps around Europe and the Middle East.

She says: “I was a constant witness to the creation of historical documents. I wanted to know who decided what records of any given event survived. I was curious to know how anyone might archive the records of displaced peoples and who had access to those records.”

She is particularly interested in the impact on children in displaced families and on the complexities of their legal identity. “They tell us the longer story about how these issues translate generationally,” she says.

She is particularly interested in the impact on children in displaced families and on the complexities of their legal identity. “They tell us the longer story about how these issues translate generationally,” she says.

For her PhD, she is following the trajectories of several individuals on the loyalist side in the American Revolution, to recover a diverse cohort of people who claimed both American citizenship and British subjecthood in its aftermath. Broadly conceived, it is an intergenerational study of the refugee experience at the inception of the modern nation-state, with a particular focus on the production of national identity among displaced peoples. Shealynn is intrigued by both the longer-term impact on record-keeping and what the test cases reveal about the early utility of Anglo-American cooperation despite the ongoing antagonism between the two countries.

She states: “It is my belief that the questions we ask of the past inform the questions we ask of ourselves.”

Childhood

Shealynn was born and raised in Denver, Colorado, with her two brothers. Her father was an engineer and her mother was a teacher, school administrator and later marriage counsellor. Shealynn attended her local schools where she enjoyed her studies and coupled them with intensive ballet training. She did ballet three hours a day after school, five to six days a week for most of her childhood. That meant ballet became her social life when she was growing up. Her ballet school was connected to a professional dance company and she and her peers performed in many of the ballets.

Shealynn always loved history, although she was also very good at maths. In the fifth grade, aged around 11, she recalls doing a creative research project on diary entries written by famous historical women such as Marie Antoinette the night before they died. “I took it very seriously. I thought it was my magnum opus,” she laughs. “I had no sense of what a historical document was at the time, but I was interested in people in history and about what they were thinking.”

Undergraduate studies

When she started her undergraduate studies at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio, she initially majored in Creative Writing, and then briefly Anthropology before finally gravitating back to History. Because the American system allowed it, she was able to take classes in lots of different subjects and completed a second major in Classical Humanities, with a minor in Art and Architecture History.

For her end of course thesis, Shealynn studied the use of classical discourse during the US Civil War to justify slavery, for instance, the way some of those on the side of the Confederate States in the South framed the conflict as similar to the Peloponnesian War between Athens, Sparta and their allies. “I was interested in how they sought to create a sense of national identity through a lens of shared history using older classical narratives to establish what they saw as the intellectual legitimacy of the Confederacy,” says Shealynn.

Refugee camps

She graduated in 2015 and, although she was keen to pursue further studies, Shealynn wanted to take some time out to explore the world. She worked briefly at a museum in Denver before being put in touch with a Christian organisation that facilitated voluntary work abroad. She started teaching English and ended up working in a makeshift refugee camp in Idomeni, on the Greek border with Macedonia.

The conditions there were very bad. The camp was originally set up for hundreds of people, but thousands arrived and were caught in a bottleneck on the border. Many had no paperwork. There were lots of children and newborn babies. Shealynn worked with a small team of people to organise the distribution of food and clothes. “I was 22, but I could see how quickly the system could break down if it was not properly managed. We set up the distribution system in a way that worked for the people and the government,” she says.

The conditions there were very bad. The camp was originally set up for hundreds of people, but thousands arrived and were caught in a bottleneck on the border. Many had no paperwork. There were lots of children and newborn babies. Shealynn worked with a small team of people to organise the distribution of food and clothes. “I was 22, but I could see how quickly the system could break down if it was not properly managed. We set up the distribution system in a way that worked for the people and the government,” she says.

She returned to the US early after her mother became sick and remained home for a year. After her mother died, Shealynn began travelling again, volunteering in several different countries, which included working with refugees again in Paris and Lebanon.

By 2018 she was applying for graduate school. She was interested in studying archive management in part because she saw in the refugee camps that documentation was a crucial factor in what was or wasn’t possible. “I worked a lot with children in Lebanon. They would create astounding artworks that were so descriptive of the conflicts they had lived through. I wondered who would see them and how anything important gets collected if you are displaced, who decides what is important,” she says. “I became very interested in the record-keeping process and how that dictates who is included in history and who isn’t.”

From master’s to PhD

Shealynn returned to the US to Simmons University in Boston where she simultaneously did a master’s in Library and Information Science and a master’s in History, starting in 2019. Within a few months, Covid hit, but Shealynn decided to stay in Boston.

She began working at the John G. Wolbach Library at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in September 2019 as the Collections Assistant where she contributed to the management of historical collections and circulating materials. Her responsibilities included the curation of two exhibits for the library’s on-site display cases, one focused on marginalia in the Wolbach’s circulating collection and the other on the history of glass plate photography at the Harvard College Observatory. She similarly contributed to an accompanying digital exhibit using ArcGIS StoryMaps software.

She began working at the John G. Wolbach Library at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in September 2019 as the Collections Assistant where she contributed to the management of historical collections and circulating materials. Her responsibilities included the curation of two exhibits for the library’s on-site display cases, one focused on marginalia in the Wolbach’s circulating collection and the other on the history of glass plate photography at the Harvard College Observatory. She similarly contributed to an accompanying digital exhibit using ArcGIS StoryMaps software.

Because of her work there and other archival access constraints during Covid, she did her master’s dissertation on the history of the standardisation of longitude between the US and UK, with a particular focus on the astronomer Phillip Sidney Coolidge, the great grandson of Thomas Jefferson, who conducted a series of chronometric expeditions between Boston and Liverpool in the 1850s.

Once again, Shealynn’s interest was in nation building, this time in relation to scientific imperialism and the United States’ westward expansion across the North American continent. Shealynn became very interested in Coolidge’s background and how it facilitated an expansive outlook. He had lived a lot of his life abroad, was educated in Europe and his parents were involved in trade with East Asia. “I found the tensions in his character interesting, the threads of what it means to be American,” she says.

One of her colleagues at the Wolbach Library was Rebecca Charbonneau, a Gates Cambridge alumna. Shealynn decided to contact the University of Cambridge about her PhD proposal which had grown out of her work in the archives. She says modern archival practice dates back to the French Revolution, and so it is structurally tied to the nation as a means to legitimise national or federal practice.

“I kept being bothered by the question of what happens to people who do not fit within nations,” she says. She was doing part-time collections care work for Historic New England at the time at the Codman Estate in Lincoln, Massachusetts, which once belonged to a loyalist family that fled to Antigua during the American Revolution. “One loyalist family member was a really prominent person in the colony and then when he left he became a nobody, dying in obscurity. There are almost no records about him after 1775 despite the family having a lot of papers documenting their history,” says Shealynn. “During the Revolution, up to 100,000 people became refugees, so we have a kind of loyalist diaspora within the British Empire of people who had only ever been British in an American context.”

“I kept being bothered by the question of what happens to people who do not fit within nations,” she says. She was doing part-time collections care work for Historic New England at the time at the Codman Estate in Lincoln, Massachusetts, which once belonged to a loyalist family that fled to Antigua during the American Revolution. “One loyalist family member was a really prominent person in the colony and then when he left he became a nobody, dying in obscurity. There are almost no records about him after 1775 despite the family having a lot of papers documenting their history,” says Shealynn. “During the Revolution, up to 100,000 people became refugees, so we have a kind of loyalist diaspora within the British Empire of people who had only ever been British in an American context.”

Shealynn started finding records of children who described themselves as dual-nationals, more than a century before dual-citizenship was a legal possibility in either country. “I was fascinated by the long-term effects of displacement and the people who are antithetical to national binaries. Where do you find them in the records? What identity do they have?” she asks.

She started her PhD in 2022, under the supervision of Professor Nicholas Guyatt, who she says has been very supportive and has pushed her to develop her ideas fully. Her dissertation reconstructs the lives of several refugee children who fled colonial Massachusetts with their loyalist parents. She is “particularly concerned with the production of national identity, the extraterritorial negotiation of political sovereignties, and the early history of cooperative action between Britain and the United States abroad”.

When she has finished her studies, Shealynn is excited to think more critically about contemporary archival practice and the ways records are collected. “I want to look at what we do with silences in the archives and how we mitigate those silences,” she says.