Willa Lane talks about her research on cuttlefish cognition and camouflage and about the similarities between human and cephalopods' ways of learning.

By studying cephalopods I am interested in exploring the multiple forms that intelligence takes. Ultimately, I hope this will have a ripple effect in terms of how we understand intelligence in a more holistic way.

Willa Lane

“Cephalopods are beautifully strange animals that look like nothing else on Earth, but they are very smart. Hearing that can be eye-opening for some. I hope to leverage that unexpectedness to make people think more deeply about what it means to be intelligent,” says Willa Lane, whose PhD explores cognition and camouflage of cuttlefish.

Humans and cephalopods, such as cuttlefish and octopuses, last shared a common ancestor over 530 million years ago. After that, they went down separate evolutionary paths, and today the animal kingdom is split into two branches: vertebrates (including humans) and invertebrates (including cephalopods). But despite this bifurcation, humans and cephalopods have evolved to display certain similar forms of intelligence.

Willa says cephalopods are really good at learning, at navigating space, have a good memory, can understand basic concepts such as the difference between odds and evens and are able to delay gratification and to generalise to new situations. “It’s really remarkable because they are so distant from us,” she states.

Origins of intelligence

Willa believes that understanding why cephalopods are so smart will help us to comprehend the origins and evolution of intelligence. Willa is particularly interested as she has ADHD and Tourette Syndrome, and she feels neurodivergent people can be treated as less intelligent than others. “By studying cephalopods I am interested in exploring the multiple forms that intelligence takes,” she says. “Ultimately, I hope this will have a ripple effect in terms of how we understand intelligence in a more holistic way. Some humans and animals are better at some forms of intelligence than others. Everyone has their own strengths.”

Willa believes that understanding why cephalopods are so smart will help us to comprehend the origins and evolution of intelligence. Willa is particularly interested as she has ADHD and Tourette Syndrome, and she feels neurodivergent people can be treated as less intelligent than others. “By studying cephalopods I am interested in exploring the multiple forms that intelligence takes,” she says. “Ultimately, I hope this will have a ripple effect in terms of how we understand intelligence in a more holistic way. Some humans and animals are better at some forms of intelligence than others. Everyone has their own strengths.”

Willa’s PhD in Psychology at Cambridge’s Comparative Cognition Lab focuses on cognitive processes such as learning and memory in cuttlefish, as well as camouflage. Cuttlefish are very sensitive, and their skin reacts to any perceived threat or change in their environment.

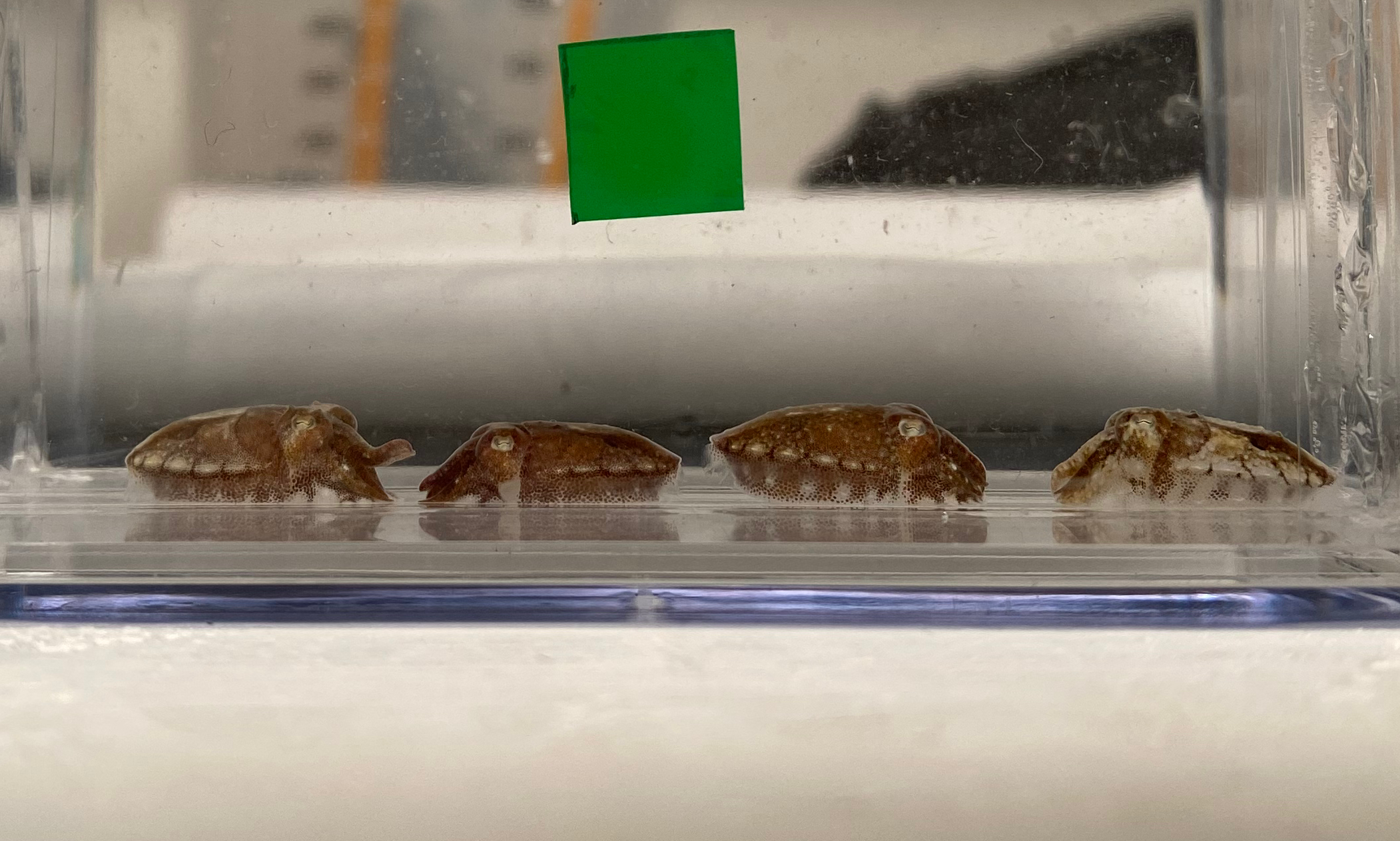

Because there are no suitable facilities to keep them in Cambridge, Willa has been doing research at the Marine Biological Association in Plymouth and this summer, as a visiting researcher at the University of Caen in Normandy, she has been carrying out a study on a group of over 200 hatchlings that are less than a week old.

She observes how they react to social and non-social environmental cues and how this affects their camouflage.

When cuttlefish first hatch, they likely live as a group together for their first few days or weeks of life. They may even change skin patterns as a group before they disperse and become more solitary. That was the focus of Willa’s study. She says she was only able to do this research thanks to the support of Gates Cambridge.

When cuttlefish first hatch, they likely live as a group together for their first few days or weeks of life. They may even change skin patterns as a group before they disperse and become more solitary. That was the focus of Willa’s study. She says she was only able to do this research thanks to the support of Gates Cambridge.

“One of my favourite parts,” she adds, “was that we were able to release them into the wild when we finished. Watching them settle into the tidepools, changing colour to match the rocks and sand, felt very full circle. I was there when they hatched, and although I only spent a short time with them, it was very moving to see them beginning their lives as wild animals after their time in the lab.”

Cephalopod cognition

Willa’s supervisor is Professor Nicky Clayton who is known for her work on bird behaviour, but who has more recently expanded her research interests to include cephalopod cognition. Willa, who did her undergraduate degree in the US at the University of Delaware in Marine Biology, feels very lucky to have got the Gates Cambridge Scholarship and says this accelerated her plans to further her studies.

Willa [2023] will be presenting some of her findings at the 2026 Cephalopod Neuroscience Conference in the US in February, supported by Gates Cambridge’s academic development funding. It will be the first time she presents her PhD work outside Cambridge, and she will give a short talk on her work in France.

Why are cephalopods so smart?

There are many theories about why cephalopods have evolved remarkable intelligence, with the main reason likely to be to avoid predation. Their camouflage is likely to have evolved for the same reason. But Willa says we still don’t fully understand why they are intelligent, why they’re so good at camouflage or how these things may be linked. “They are really embodied in terms of the ways they move through the world. They are very driven by their senses, particularly vision, and they can change the colour of their skin within a fraction of a second,” she states.

There are many theories about why cephalopods have evolved remarkable intelligence, with the main reason likely to be to avoid predation. Their camouflage is likely to have evolved for the same reason. But Willa says we still don’t fully understand why they are intelligent, why they’re so good at camouflage or how these things may be linked. “They are really embodied in terms of the ways they move through the world. They are very driven by their senses, particularly vision, and they can change the colour of their skin within a fraction of a second,” she states.

No other animal can change their appearance as quickly as a cephalopod, not even chameleons. “In this sense, cephalopod camouflage can provide a read-out of an individual’s internal state, so they’re sort of wearing their thoughts on their skin,” says Willa. “In that way, they’re almost like artists, creating a representation of their impression of the world around them.”

A mesmerising presence

Willa was drawn to cephalopods from an early age. She grew up in the mountains of Vermont with a deep love of nature and spent holidays on the coast with her grandmother, including long hours at the local aquarium. She would sit for hours watching the octopuses, mesmerised.

Willa was drawn to cephalopods from an early age. She grew up in the mountains of Vermont with a deep love of nature and spent holidays on the coast with her grandmother, including long hours at the local aquarium. She would sit for hours watching the octopuses, mesmerised.

“Most of the time they would sit still, like they were asleep, but every so often they would move and spread their arms, showing their suckers and changing their skin colour,” she says. “My parents always had a hard time pulling me away.”

She would ask the aquarium staff questions and soon realised that every octopus was very unique and had their own temperament. From that point on she was keen to study what made octopuses so individual.

Now those questions have come full circle with her research on cuttlefish behaviour. “I have done what I was always dreaming to do,” she says.