Mohammad Shomali is an imam whose research will focus on the human rights of non-Muslims in Islamic law.

Cambridge offers an amazing opportunity to listen to all sides of the story.

Mohammad Shomali

When he was a child, Mohammad Shomali met several religious leaders, including the Pope. The meetings came about because his parents ran a lot of interfaith dialogues between Muslims and Christians. “From a very young age I have had a passion for bringing people together from different faith groups,” he says.

That passion has driven his studies: his MPhil in Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Cambridge where he has focused on Jewish Muslim relations and his PhD, which he begins in the autumn, which will look at Islamic law and minority human rights.

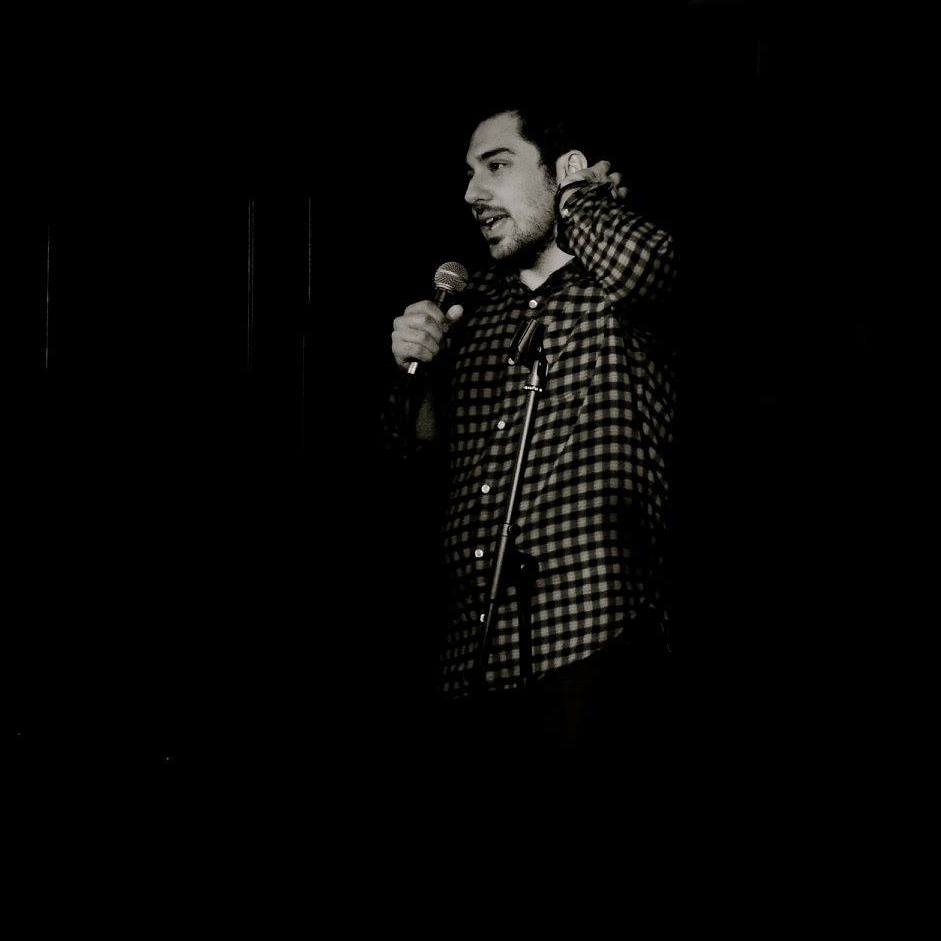

Mohammad, an imam who has led workshops in Africa which aim to give young people the skills they need to confront extremism, has also used stand-up comedy to counter stereotypes in the UK and bring people from different communities closer together.

Childhood

Born in Isfahan, Iran, his family moved to the UK when he was five so his father could do a PhD. Though they returned to Iran later, Mohammad was sent back to the UK to do his GCSEs at a private school in London. He did very well in his exams, getting the top mark in the capital for maths, and the plan was for him to stay on to do A Levels and maybe take up a career in finance.

However, over the summer after his GCSEs Mohammad began to ask himself deep philosophical and spiritual questions about what life was about and, after much soul searching, decided that he wanted to forego A Levels and return to Iran to study to be an Islamic cleric at the Islamic Seminary in Qom. “It was a very difficult decision,” he says. “Initially I wasn’t sure what I was doing, but I came to see it was a good decision in time. It was a culture shock moving from a school in the UK to pursue Islamic Studies in Iran, but with time I got used to it.”

Mohammad says that, although he grew up in a religious family, he was not very religious himself as a child. “It was more that I started asking myself questions and looking for answers. Many people were surprised at the direction I took, including my parents,” he says. “But I was always asking why as a child. I wanted an explanation for everything. It’s just that the questions got bigger after my GCSEs and I started question the point of life and my role in it.”

A religious life

The culture at the seminary was very different to what he had been used to, from what people wore to the way they talked to what they valued. Mohammad quickly adapted to his new circumstances. “Everyone was very focused on learning and on purifying themselves,” he says. “Everyone was working towards the same goal. They were very committed and keen to be nice to each other. It was very much ethically based. Students had a passion to become better people. It was inspiring.”

For the first year he boarded at the seminary during the week, but the following year he went home more frequently to help his mother with his brother, who has muscular dystrophy, while his father was away for work.

After three or four years he started teaching and from 2009 he began travelling to Africa for a few months at a time to teach with the International Institute for Islamic Studies. He went to Tanzania where he learnt Swahili so he could communicate directly with the people he taught English, maths and science to. He also worked with other volunteers including doctors and engineers.

Mohammad realised that students in one of his classes were being targeted by the Islamic extremist group Boko Haram. He says extremist groups were going from village to village recruiting young children so he decided to work with colleagues to give workshops to teach them the communications skills they needed to be able to resist extremism: the ability to think rationally and critically. “The aim was to make sure they were safe from being brainwashed by extremists,” says Mohammad.

The workshops were given in Tanzania, Kenya, Rwanda and Uganda. Mohammad says a few of the students said they had left Boko Haram because of his work. There are still two teachers in Tanzania continuing the workshops.

Mohammad’s studies lasted eight and a half years as he did two years in one and he finished last June.

Cambridge

In his last year, Mohammad applied to do a master’s in Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Cambridge focusing on Muslim Jewish relations and in particular on the Israeli Palestinian conflict from the point of view of Jewish scholars. “Cambridge offers an amazing opportunity to listen to all sides of the story,” he says. He has had access to original documents from the Fatimid empire which tell the story of Jewish daily life in a Muslim state and which he says have changed the way scholars think of the era.

During his MPhil he became very passionate about the human rights of non-Muslims in Islamic law and teaching, an issue he says is very relevant at the current time and which he wants to form the basis for his PhD. He believes it is critical to be able to confront ideologies such as that of IS and to show that they have no rational or religious basis. That requires a rigorous attempt to understand the core of the problem. “Without that understanding there can be no proper solution,” he says.

While he has been at Cambridge, Mohammad has also been involved in confronting stereotypes about Iran, the Middle East and Muslims in a very direct way through performing stand-up comedy around the university. “It’s another way of bringing people closer together,” he says. “I want to show that Muslims can be funny and use comedy to communicate with people about this difficult period we are living through.”

As an imam, he has also given talks to Muslim communities in Cambridge and London and is keen to debate such issues as how Islam is compatible with feminism, a subject he has been researching.

Mohammad says he has been very impressed by Gates Cambridge, its mission and diversity. When he was interviewed for the scholarship he met a Danish student who is researching muscular dystrophy. He has helped Mohammad to find out about a new treatment which may help his brother. “Already it has been a very good experience,” he says.

Mohammad Javad Shomali

- Alumni

- Iran, Islamic Republic of

- 2016 PhD Asian & Middle Eastern Studies

- King's College

Having studied and taught in the Islamic Seminaries of Iran for almost a decade, I then joined the University of Cambridge, where I completed an MPhil and PhD. in Middle Eastern studies.

I developed a strong interest for mental health and psychology and this interest brought me back to the University of Cambridge a year after the completion of my PhD. Right now I am training as studying Psychotherapy at the faculty of education.

The main focus of my research right now is the intersection between psychotherapy and spiritual development.

Previous Education

Qom Theological Centre

University of Cambridge