Eryk Salvaggio and Tristan Dot talk about the possibilities and challenges of AI art.

At the moment AI is telling us a story about what we are supposed to do with AI art, but if we take a step back and steer the system in more creative directions, which are more fair and less biased to certain groups and less exploitative of other artists, what can it do? Can we tell a different story?

Eryk Salvaggio

Eryk Salvaggio [2025] and Tristan Dot [2022] are both interested in the questions thrown up by AI art, but they come at it from different perspectives. Before Cambridge, Tristan studied both art history and machine learning. His PhD in English takes a critical approach to AI images by bringing together his technical and aesthetic expertise. “I want to understand what is going on technically, economically and politically with AI images,” he says, adding that he is comparing the current digital, visual culture with 19th century designers who lived at a time of similar technical and artistic exploration.

Eryk, who is doing a PhD in Digital Humanities, says his approach is more grounded in artistic practice than in machine learning. “I know enough to raise questions about the technical elements of AI which can be opaque, but I’m looking at it through a lens of the humanities and art making,” he says. When it comes to archiving, for instance, he says genAI tends to work in reverse to the normal process in the humanities, that is, it takes the data, clumps it together and ‘blurts’ it back out without any contextualisation. He wants to explore the role that arts and humanities can play in recontextualising that data and in highlighting the process that is going on.

He calls it ‘filling in the blanks’. “We have a tendency to call the part of the process of producing AI art that we don’t understand creativity. What I see is just gaps that the AI fills in carelessly. I want to look at how we put care back into that process,” he says.

AI art

Both Tristan and Eryk have made their own AI art. Tristan has used his art to explore academic questions, for example, he used CCTV images to explore political questions about surveillance culture. Eryk has been involved in experimental art since he was 15 and his PhD will produce frameworks that examine assumptions about the use of generative AI in policy, pedagogy and design.

For Tristan, art is about getting away from the usual way of seeing things and exploring new ways of interpreting reality. However, after an initial explosion of creativity, he feels Big Tech is co-opting AI art in a simplistic and normalising way that limits its aesthetic possibilities.

For Tristan, art is about getting away from the usual way of seeing things and exploring new ways of interpreting reality. However, after an initial explosion of creativity, he feels Big Tech is co-opting AI art in a simplistic and normalising way that limits its aesthetic possibilities.

He thinks there are parallels with the 19th century in that AI and genAI have moved from smaller models with greater creative potential to larger, more fixed forms. In the same way, photography in the 19th century was influencing painting and art in many different ways until it slowly became more industrialised and less experimental. Textile designers faced many of the same questions as today’s AI artists over ecology, copyright, colonialism and repetition, he adds. He is also interested in wider contextual issues and says discussions with Gates Cambridge Scholars and others at Cambridge have helped reframe his ideas about the production of images.

Eryk recalls having worked with smaller generative adversarial networks [GANs] in the past. GANS are a type of machine learning algorithm that can generate new, previously unseen data that is similar to existing data. He recalls feeding GANs thousands of photos he had personally collected. Now, he says, the AI works on vast amounts of data and there is a more distant relationship between artist and data which ‘mimics commodification culture’. “GANS was like an artistic scene with individuals working on niche projects,” he says. “Now everyone has access to the same tool and it is more fixed. You can’t colour outside the lines. You are blocked out of certain types of learning and art is getting scooped up and commercialised.”

But it’s not too late to change it, he says. Eryk is interested in discovering how AI can be used to explore new opportunities for storytelling and expression rather than just reproducing art based on data inputs from what has been before. “I’m interested in the question of why we should use AI to make art,” he says, adding that it is about how AI can liberate artists.

But it’s not too late to change it, he says. Eryk is interested in discovering how AI can be used to explore new opportunities for storytelling and expression rather than just reproducing art based on data inputs from what has been before. “I’m interested in the question of why we should use AI to make art,” he says, adding that it is about how AI can liberate artists.

“At the moment AI is telling us a story about what we are supposed to do with AI art, but if we take a step back and steer the system in more creative directions, which are more fair and less biased to certain groups and less exploitative of other artists, what can it do? Can we tell a different story?”

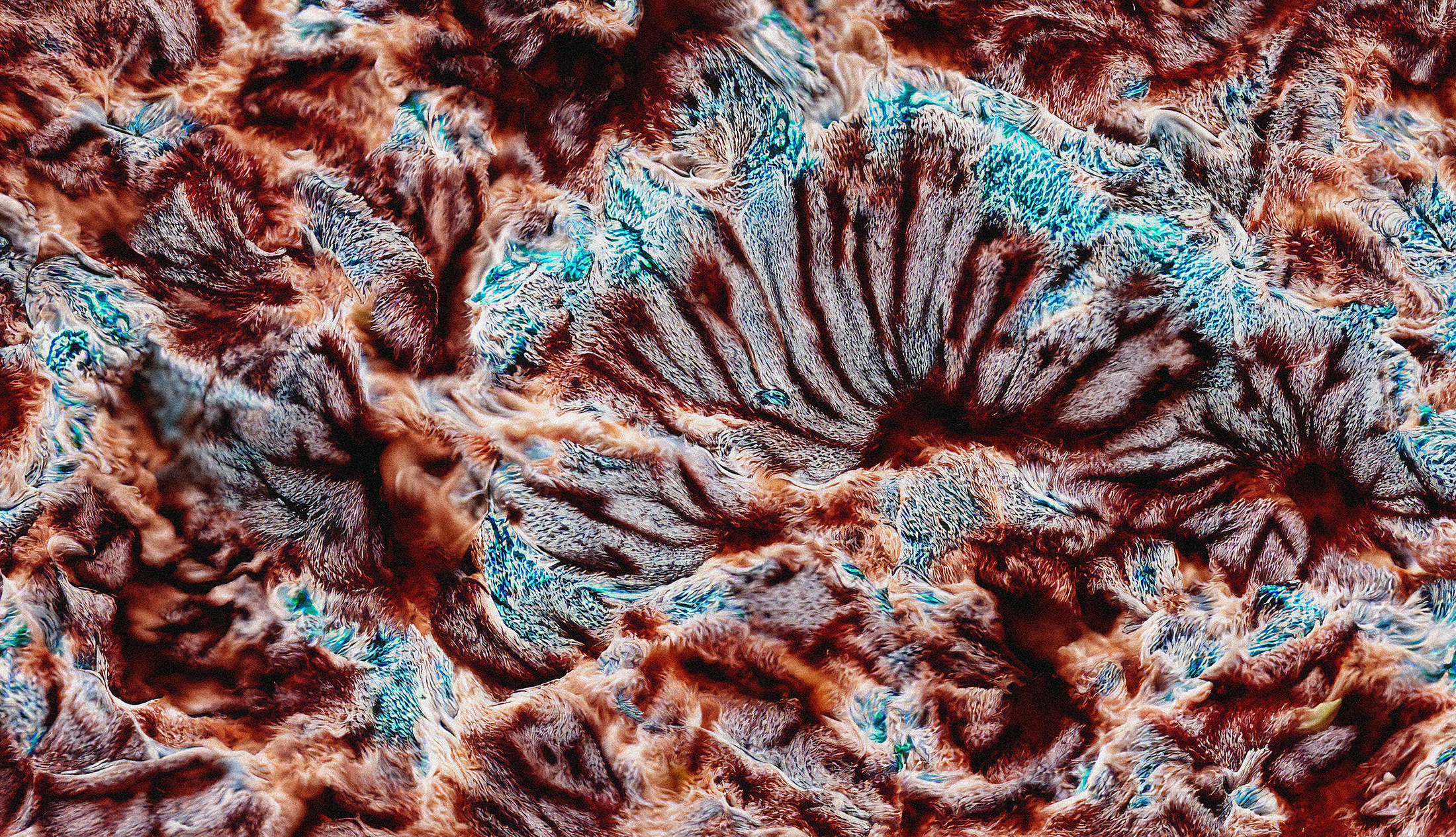

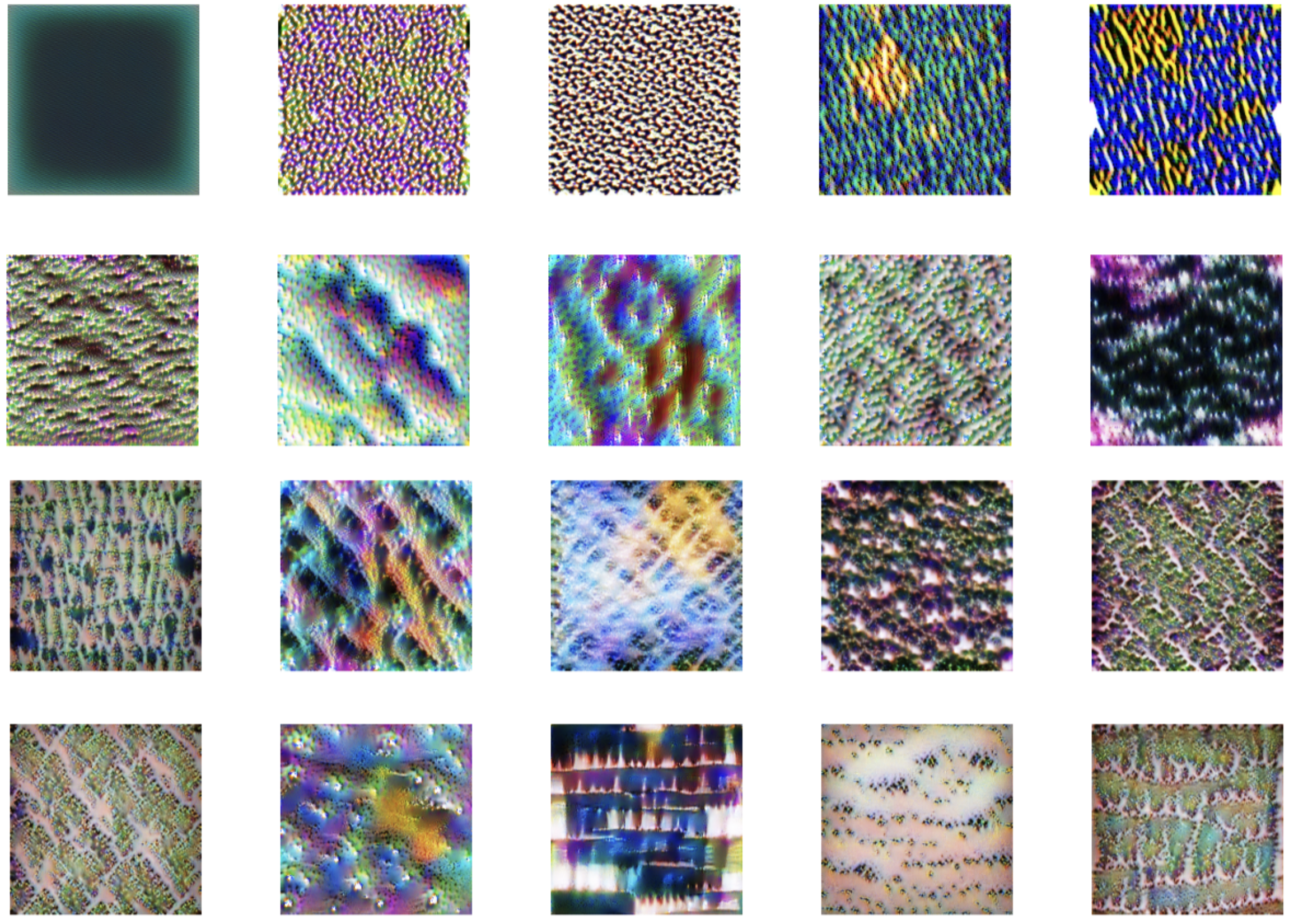

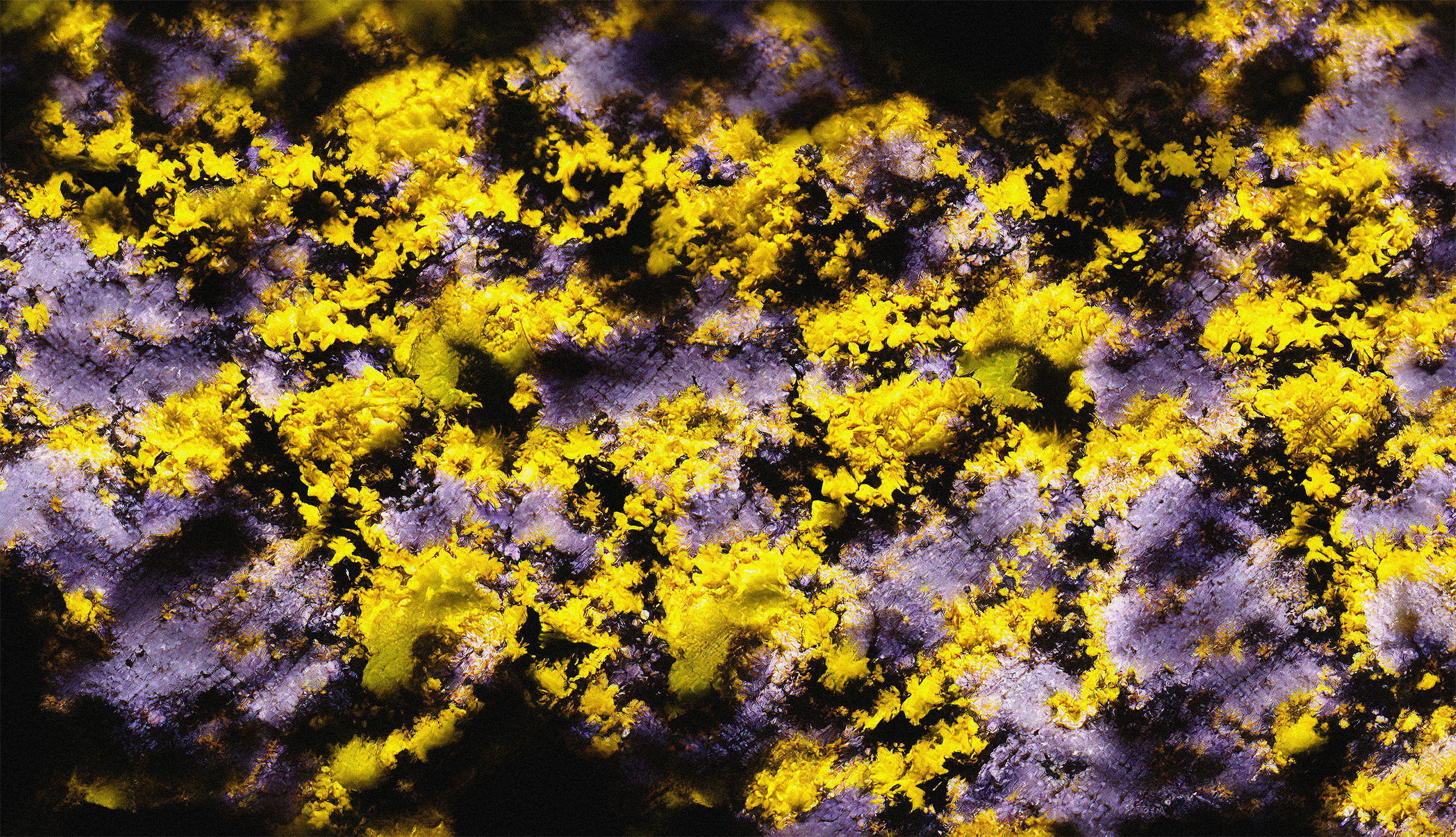

*Artist Eryk Salvaggio’s Pollen Series [top picture and above left] uses AI image generators trained exclusively on public domain materials to produce images of ‘noise’ and ‘pollen’. Tristan’s Visualisations of a neural network’s learnt features, after fine-tuning on textile patterns is pictured above right].

**An edited version of this interview appears in the Gates Cambridge 25th anniversary magazine, which is just out here.