Hosna Jahan's research focuses on the impact of women's purdah practice and development in Bangladesh.

The practice of purdah and the negotiation of its limits have important implications for women’s economic contribution and development.

Hosna Jahan

Hosna Jahan [2013] grew up travelling between Bangladesh and Australia. It made her question why policies that worked in some countries didn’t work in others and focus on addressing issues of social justice. She says: “I grew up seeing poverty at first hand. You can either see these things as natural or tragic. I travelled between developed and developing countries and it made me think why, for instance, some groups of people do not thrive in the education system in Bangladesh when they thrive elsewhere. It made me think this is not a tragedy; this is due to systematic injustice and I wanted to do something about that.”

It was this that brought her to Cambridge where she learnt the research tools she will need when she starts her PhD in the autumn which will focus on understanding Muslim women’s purdah practices and their impact on development initiatives in Bangladesh. She says: “The manifestations of purdah can range from sartorial practices of women wearing various forms of veil to imposing severe restrictions on a woman’s movement outside her immediate homestead. In its most conservative forms, purdah can extend to imposing prohibition on women’s voice and with whom they are permitted to converse and the practice of eye avoidance.”

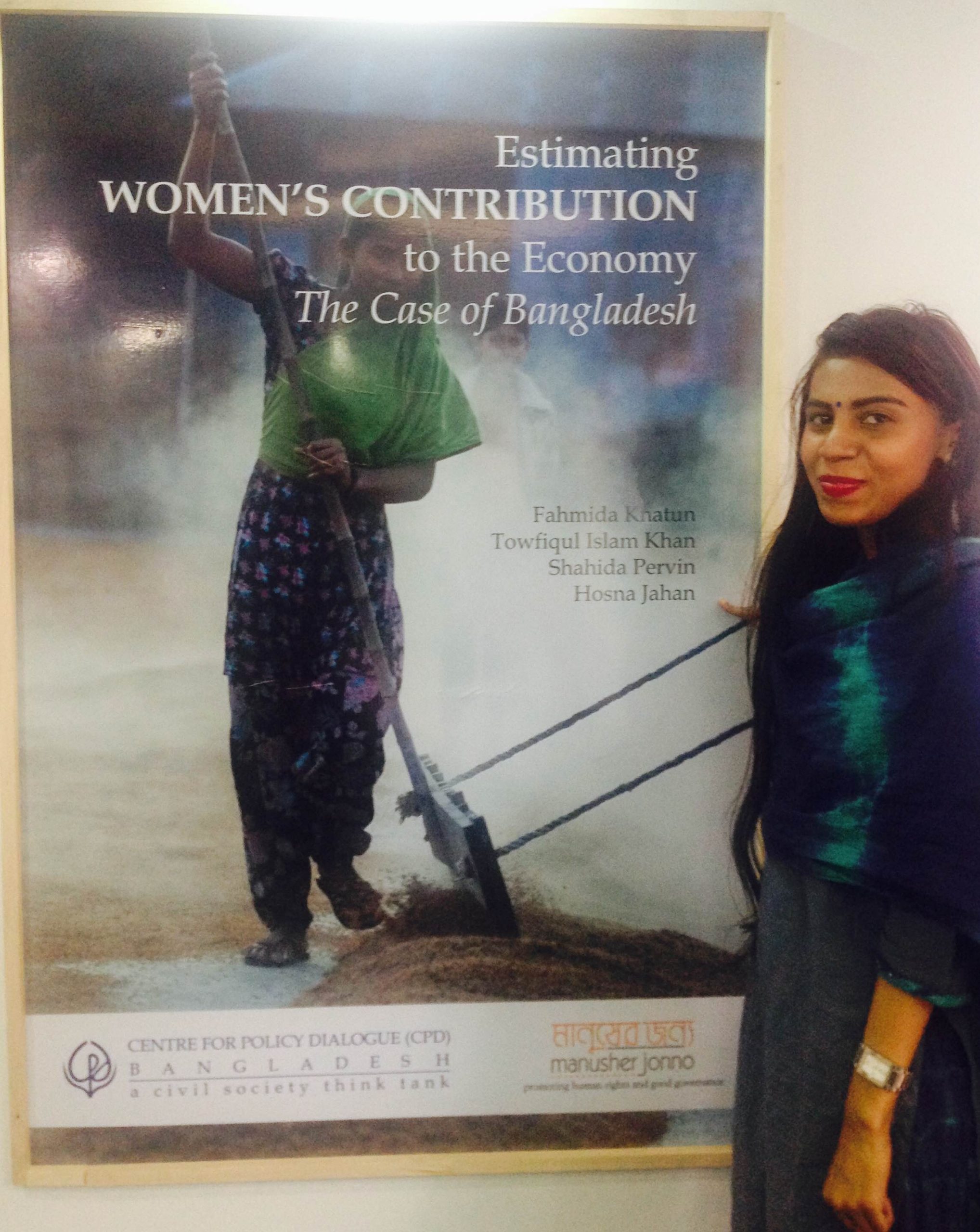

Hosna, who has co-authored a book on women and development in Bangladesh, Estimating Women's Contribution to the Economy: the Case of Bangladesh, is interested in the complexities of the meaning and practice of purdah in Bangladesh and how it affects women’s everyday lives. She says: “The practice of purdah and the negotiation of its limits have important implications for women’s economic contribution and development in two major ways. First, it determines the economic opportunities available to women. By imposing restrictions on women’s mobility, it limits their access to the public space, such as the market and many other economic opportunities, which hinders their economic autonomy. In this way, it determines their access to the labour market, the nature of work available to them, and the location and hours of their work. “Second, the practice of purdah determines women’s capability of spending. For a traditional Muslim Bangladeshi woman, strict observance of purdah and a failure to negotiate the limits of purdah is likely to constrain her access to markets and autonomy, thus restricting her efficient conversion of income into well-being.”

From science to micro finance

Hosna was born in Chittagong in Bangladesh. When she was 10 her mother had a serious car accident causing her to lose her memory. “It was a formative part of my childhood,” she says. She was sent to boarding school in Australia and says she loved it there and made friends for life. “In Bangladesh I was always protected by my family. Being at boarding school in Australia helped me to be independent and more disciplined,” she says. The boarding school was Catholic and very different from the curriculum in Bangladesh. Hosna became interested in philosophy and comparing different religious traditions. However, she mainly focused on science.

From an early age she had wanted to be a space engineer. “I loved the stars and wanted to build a spaceship and go to the stars,” she says. When she left school she enrolled on a Science programme at the University of Sydney. At the same time, she started trying out Arts courses, including French art and culture, international relations and political economy. “For me science was all about answers, but all of a sudden I was in a whole world of maybes and different ways of thinking about things,” she says, “debating political priorities and ethics.”

In her final year Hosna did her dissertation on micro finance in Bangladesh and women’s empowerment. She conducted field work close to her parents’ village, talking to women about how they used microfinance. “Huge claims were being made for microfinance, that it was helping women become empowered, but there are many different models of microfinance and many ways of being empowered,” she says. Hosna graduated in 2012 with two degrees, one in Science, majoring in Chemistry, and one in the Arts, majoring in International Relations and Political Economy, and with a desire to work in development in Bangladesh. She applied for an MPhil in Development Studies at Cambridge and began her course in 2013. She says she learned a lot from the course about different types of economics. “It gave me the tools I needed to do further research,” she says. Gates Cambridge was “the best thing that happened to me as it brought me into a small but close-knit society”.

Since she returned to Bangladesh she has been working with several charities and has been linking up with two village schools where she gives regular talks. She says: "I never realised how much seeing a young woman give a speech at a school event could inspire other young people and their parents.”

Hosna hopes her PhD which she begins at the London School of Economics this autumn will contribute to fulfilling the Gates Cambridge mission of improving the lives of others by investigating the role of religion in women’s socio-economic development. It will examine questions such as the impact of donning “modest attire” (such as the hijab or burqa) in public spaces has on women’s participation in the labour market, higher education and political participation and what the relationship is between women’s choices around purdah practices and their ability to sustain vital informal socio-economic networks. Hosna is interested to find out what “renegotiating purdah” norms might mean for Muslim women and how they might do that. Hosna says: “My research aims to broaden the space for discussion around women’s choices and development practices, while also indicating ways to formulate effective policies that will acknowledge the difference in Muslim women’s lived realities and improve accessibility for them to fully participate in the process of development.”

Hosna Jahan

- Alumni

- Bangladesh

- 2013 MPhil Development Studies

- Queens' College

Originally from Bangladesh, I graduated from the University of Sydney with a double degree in Science/Arts, reading Chemistry, Government and International relations, and Political Economy. During my Honours year, I examined the extent to which microfinance (small loans) empower women to achieve development outcomes. My degree in Cambridge was an interdisciplinary professional training and research combination course in development and economic policy. At present, I am pursuing PhD at LSE under the supervision of Professor Naila Kabeer. My primary research interest is in gender policies and economic development.