Yu Huang brings a wealth of different perspectives to her PhD in Earth Sciences on the contribution of methane gas to climate change.

All the philosophical questions debated in the 20th century were done through traditional disciplines, but there are so many metaphysical questions that we still need to tackle and these require multiple disciplines to break through the philosophical barriers. I am so lucky to think about these questions from multiple lenses. We have exhausted traditional methods. We need new ways.

Yu Huang

Yu Huang’s PhD in Earth Sciences investigates the ancient historical roots of methane rise and its contribution to climate change. She brings a wealth of different perspectives to her studies, having started with a degree in Geography, followed by a more mathematical turn for her master’s and finally arriving at paleoclimatology.

Her whole academic career has been fuelled by intellectual curiosity about the big metaphysical questions and a desire to probe those questions from multiple perspectives, including art. Her love of art has been a constant and she refused to give it up and focus solely on science. She is keen not to conform to any disciplinary expectations and wants to push the boundaries.

“The 20th century was characterised by violence, chaos, dehumanisation and destruction,” says Yu [2025]. “All the philosophical questions debated in the 20th century were done through traditional disciplines, but there are so many metaphysical questions that we still need to tackle and these require multiple disciplines to break through the philosophical barriers. I am so lucky to think about these questions from multiple lenses. We have exhausted traditional methods. We need new ways.”

Childhood

Yu was born and grew up in Shenzhen in southern China. Her father is a car engineer and her mother an accountant. She was largely brought up by her grandmother, who grew up in extreme rural poverty in the 1950s. Yu’s grandmother, who lost her parents at a very young age, never had the opportunity to attend school. Despite this, she deeply valued education and impressed upon Yu from early childhood the importance of pursuing knowledge.

She has a younger sister who is studying in China. Yu says her primary school was initially led by a head teacher who was very visionary and experimental. Learning was through play and exploration. After primary school she moved to a leading secondary school that specialised in foreign languages, having passed an entrance exam. At the time Yu’s main desire was to become an artist. She would bring her large sketch books and colouring pencils to school and would draw or paint every day. Her love of art had begun at primary school where she played a video game which involved exploring other planets with fantastical, friendly creatures. She started copying the images from the screen and went from there, exploring non-human creatures based on where her imagination took her.

Yu was good at all subjects and really enjoyed combining the arts and sciences throughout her time at school. She says she has three brains: one for art, one for humanities and one for science. However, she faced a lot of barriers to studying art, which only made her more determined not to give up. Her friends were very supportive. Meanwhile, her teachers supported her in other ways. Her physics teacher encouraged her science studies and because she was so inspired by physicists, Yu told her friends at the age of 15 that she wanted to live close to the Cavendish Laboratory in the Department of Physics at Cambridge. Her teacher also exposed her to science texts in English, knowing that she was considering studying abroad. Yu’s interest in studying in the UK had been whetted first in 2015, when she travelled with her family to Edinburgh during the Edinburgh Festival and was exposed to all the street art taking place around her.

Yu was good at all subjects and really enjoyed combining the arts and sciences throughout her time at school. She says she has three brains: one for art, one for humanities and one for science. However, she faced a lot of barriers to studying art, which only made her more determined not to give up. Her friends were very supportive. Meanwhile, her teachers supported her in other ways. Her physics teacher encouraged her science studies and because she was so inspired by physicists, Yu told her friends at the age of 15 that she wanted to live close to the Cavendish Laboratory in the Department of Physics at Cambridge. Her teacher also exposed her to science texts in English, knowing that she was considering studying abroad. Yu’s interest in studying in the UK had been whetted first in 2015, when she travelled with her family to Edinburgh during the Edinburgh Festival and was exposed to all the street art taking place around her.

As she progressed through secondary school, Yu became interested in atomic physics and would read the theoretical physicist Werner Karl Heisenberg’s books. She began to question the history and ethics of science, finding it hard to reconcile the idealistic side of science as about seeking truth and knowledge and the way it could be used to meet darker political goals.

Because she was keen to study in the UK, Yu took A Levels in a small group of 20 students. Her school only offered Maths, Physics, Chemistry and Economics so Yu taught herself English Literature and Geography to reflect her wider interests. She made herself Shakespeare cards and chose her own post-modernist fiction to study, taking the exam alone in the middle of an exam hall. She chose Geography because she was drawn to the feeling, after reading several geography books, that it could tie all the different questions she had together.

Undergraduate years

She applied to Cambridge and was accepted at Corpus Christi College, next to the historic Cavendish Laboratory. She feels fortunate to have received close mentoring from Professor Christine Lane, her Director of Studies at Corpus, who showed her that it was possible to pursue rigorous, profound science with a humanistic perspective.

Through shared field trips and sustained intellectual guidance, Yu came to appreciate Geography not as a fixed disciplinary identity but as a space of unusual freedom. Her College further supported this openness through travel grants that enabled her to attend international conferences as an undergraduate, where exposure to leading Quaternary scientists led to opportunities such as volunteering on an archaeological expedition. Exchanges with leading scholars – for example, discussions that challenged and expanded her thinking around climate change – reinforced her confidence to think independently and to further develop her diverse intellectual projects.

For her master’s she turned back to her love of science, particularly quantitative methods. Her MPhil, for which she won the EFG Scholarship, was in Quantitative Climate and Environmental Science and she became completely immersed in it, passing with distinction.

Her dissertation was about the dynamics of Asian monsoons in the last inter-glacial period around 120,000 years ago. She used speleothem isotope records together with isotope-enabled Earth System Models to investigate how orbital-scale forcing drives large variations in hydroclimate and atmospheric circulation.

“I really enjoyed reading about past civilisations,” says Yu. “I had long been interested in history and I wanted to figure out the roots of our current problems. Climate change for me was about everything we did in the past and how historic and colonial inequalities still play out in the world today.” She adds that the master’s was a way for her to transition to doing ‘proper climate science’ and gain the scientific legitimacy that she wanted. At undergraduate level she did a dissertation which involved reconstructing rapid changes in deep-sea current speed during the last deglaciation using marine sediment cores. She became interested in questions around the usefulness of talking about climate tipping points rather than a crisis of human governance.

Earth Sciences research

For her PhD in Earth Sciences, Yu wants to bring her interest in science and social sciences together, believing that approaching the problem of climate change through just one lens is not sufficient. She says she is happier with her studies now. “I feel my Cambridge has started now,” she says. “Now I get to produce knowledge that I am interested in, not just consume it.”

The focus of her thesis is the story of atmospheric methane variations in the past 10,000 years. She is building on the hypothesis that methane levels began rising as early as 5,000 years ago due to human action, namely, the spread of rice irrigation and livestock. Using Antarctic and Greenland ice cores, combined with Earth System Models, she will chart the interglacial evolution of methane and evaluate potential climate-methane feedback. She wants to explore the philosophical ideas of ‘natural’ versus ‘human’, and to inform cost-effective climate action.

The focus of her thesis is the story of atmospheric methane variations in the past 10,000 years. She is building on the hypothesis that methane levels began rising as early as 5,000 years ago due to human action, namely, the spread of rice irrigation and livestock. Using Antarctic and Greenland ice cores, combined with Earth System Models, she will chart the interglacial evolution of methane and evaluate potential climate-methane feedback. She wants to explore the philosophical ideas of ‘natural’ versus ‘human’, and to inform cost-effective climate action.

Yu loves that she can be creative and bring different disciplines together to figure out how the world works and how we got to this point. “I realise more and more that all the fun things are interdisciplinary,” she says.

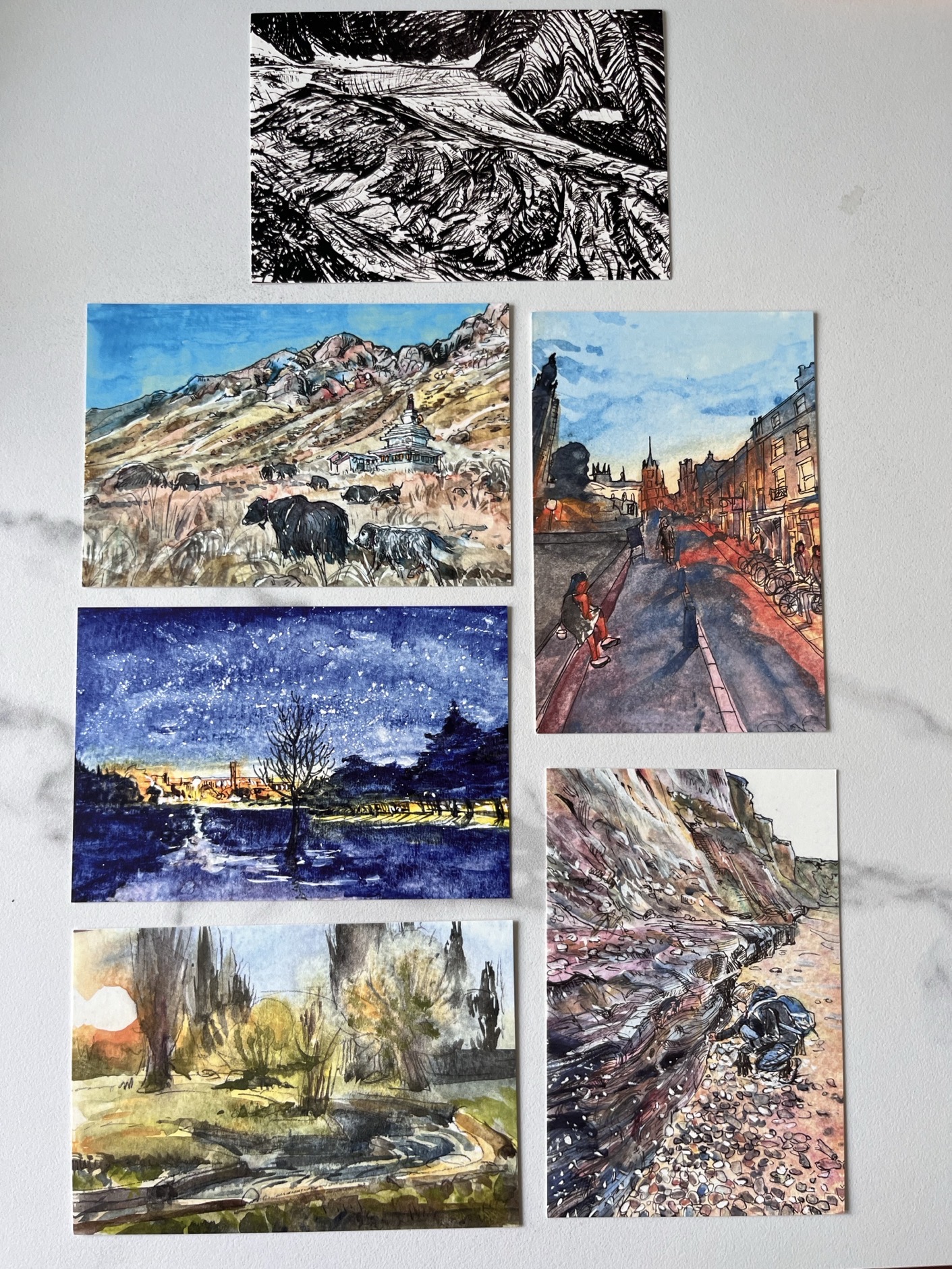

She continues to paint watercolour landscapes and do ink drawings – she has just set up a website to showcase her art – and says her research feeds her art. Her art helps her to imagine the lives of early humans. “I find beauty both in painting the natural world and in writing about it,” she states. “I think there is no separation in life.”