Gates Cambridge Scholars have been doing outstanding work to shed light on our early history, from climate change to ancient snakes.

The Gates Cambridge Scholarship covers a huge range of disciplines and celebrates how they are able to improve the lives of others. History, including ancient history, can alter the way we see the world, how we understand the past and approach the future. Here we look at the impact our Scholars are having in Archaeology.

Climate change

When it comes to climate change, several scholars have been investigating the history of climate change adaptation.

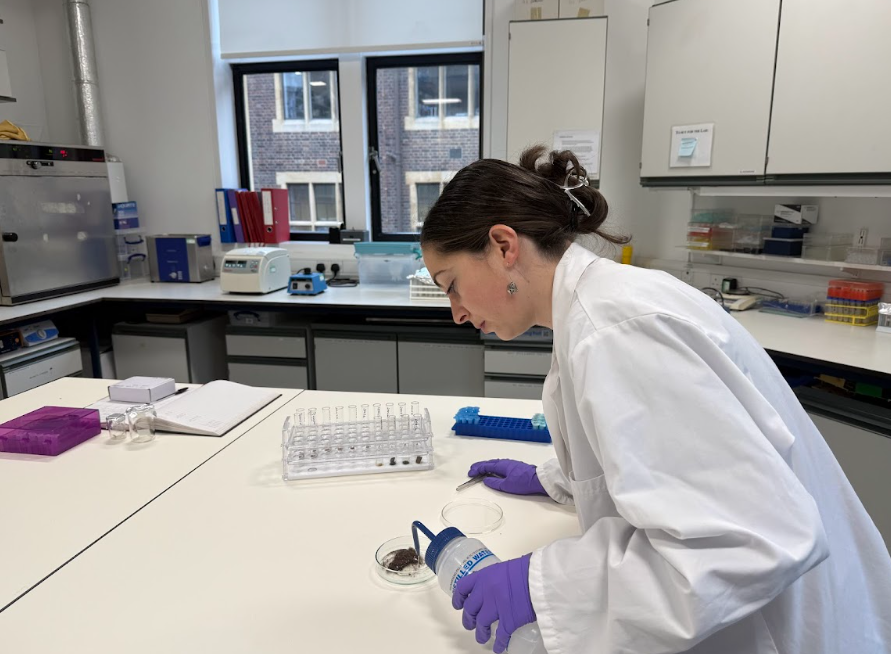

Suzanne Pilaar Birch [2008, pictured below left] is Associate Professor at the University of Georgia with a joint appointment in the Department of Anthropology and Department of Geography. She directs the Quaternary Isotope Paleoecology Lab and coordinates the Internship Programme at the Georgia Museum of Natural History.

Her current research focus evaluates how early agricultural societies adapted to climate and environmental change in the Mediterranean region, as well as themes of migration and mobility, by applying stable isotope analysis to biological remains including animal and human bones and teeth, as well as shells, and plants.

Her current research focus evaluates how early agricultural societies adapted to climate and environmental change in the Mediterranean region, as well as themes of migration and mobility, by applying stable isotope analysis to biological remains including animal and human bones and teeth, as well as shells, and plants.

In 2023, she released a 20-episode series with The Great Courses, “Early Humans: Ice, Stone, and Survival”, which is available through The Great Courses Plus, Amazon Prime, Audible, Apple TV, Roku TV, etc.

Since 2024, she has served as an expert with Smithsonian Journeys, on trips including ‘Around the World in a Private Jet’, ‘Prehistoric Cave Art of France and Spain’, and ‘Cruising the Mediterranean’, with upcoming trips including ‘Croatia’s Dalmatian Coast by Sea’, ‘Around the World by Private Jet’ (x2) and ‘The Silk Road, a Journey to Central Asia’.

She is also keen to communicate her knowledge more broadly and has a middle-grade non-fiction book coming out with MIT Kids Press in 2027. “Animal Bone Detectives” is all about her area of expertise, zooarchaeology, but aimed at a middle school audience. She hasn’t left the adults out either – she has an adult non-fiction book on archaeology under contract with Princeton University Press.

In addition, Suzanne has worked tirelessly to promote women academics in her sector. In 2013 she co-founded TrowelBlazers, an organisation dedicated to promoting the past, present and future of women in archaeology, paleontology and geology and the organisation is still going strong.

Suzanne did both her master’s and PhD at Cambridge with the support of Gates Cambridge. For her master’s she focused on changing human mobility and the transition from hunting and gathering to using domestic animals on one Adriatic island. Her PhD connected changes in diet and human mobility with environmental change in the Eastern Adriatic between 11,000 and 7,000 years ago, using isotope analysis of animal teeth.

Other Scholars have dedicated themselves to understanding the history of environmental change.

They include Stijn de Schepper [2002] and Jimin Yu [2002]. Both are paleoclimatologists, intent on tracing the impact of climate change on life in pre-human times. Using ancient DNA Stijn de Schepper looks at organisms which don’t leave behind fossil shells or skeletons, opening up an entirely new fossil record to find out if, why and how the environment changed in the past. Stijn is Research Professor at NORCE Climate and Environment, affiliated to the Bjerknes Centre for Climate Research in Norway.

Similarly, Jimin Yu’s research aims to understand how climate and ocean chemistry has changed in the distant past through analysis of miniature shells from different locations in the ocean. Jimin is Professor of the Marine Carbon Cycle at the Research School of Earth Sciences of the Australian National University.

Rachel Reckin [2014] is an archaeologist and historic preservation specialist for Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks and a Board Member of the Alpine Ecosystems Research Institute whose PhD focused on the discovery of artifacts such as basketry and arrows following the melting of alpine ice as a result of anthropogenic climate change. From 2010-2014, she was part of an interdisciplinary team of researchers, including representatives from the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes, the Blackfeet Nation, several universities and the National Park Service, who undertook a survey of high altitude ice in America’s Glacier National Park.

Eduardo Machicado [2011], from Bolivia, was briefly a professor of Amazonian Archaeology in Bolivia after leaving Cambridge, but, motivated by his developing interest in Human Ecology, he returned to the UK in 2017 and broadened the scope of his research in the archaeology of wetlands to the British Fenland.

He continued teaching in Cambridge, became a Rokos Early Career Research Fellow at Queens’ College, Cambridge, and was hired as a geoarchaeologist at the Cambridge Archaeological Unit, where he worked under the direction of Canadian archaeologist Christopher Evans and Professor Charles French.

Among the most important projects during that time was Needingworth Quarry, Cambridgeshire, where he explored Neolithic to Bronze Age occupation and evidence of large-scale environmental change, including the impact of prehistoric sea-level rise.

After this, he was offered a permanent position at the Museum of London Archaeology (MOLA), a “development-led” archaeological company and independent research organisation dedicated to establishing the significance, potential and sustainability of archaeological work within London and in major infrastructure projects. As part of MOLA, he has received a small AHRC Impact Acceleration Grant and is currently supervising a PhD student at the University of Glasgow as part of a Collaborative Doctoral Partnership Grant.

Among his current research projects, Eduardo is conducting archaeological work as part of the mitigation for the Anglian Water Strategic Pipeline Alliance project, the renovation of the Houses of Parliament and the Tideway Tunnel Archaeological Excavation.

Eduardo is also a permanent member of the board of Fundación Flavio Machicado Viscarra, a non-profit organisation working with public libraries and historical archives in La Paz, Bolivia, where he continues the work of his father and grandfather. Eduardo’s grandfather built up a library of over 30,000 books and a collection of 7,000 classical music records as well as opening up his house for weekly public music sessions – a tradition his father continued. Eduardo’s father also started a non-profit organisation in 1992 to open the library to the public, another of his grandfather’s dreams. Eduardo and his sister are keen to continue that legacy.

Eduardo told Gates Cambridge: “My grandfather passed on his emphasis on education to my dad and his desire to share the educational resources he had amassed with others who were less fortunate.”

Around the world, Scholars are investigating ancient history and its impact on their regions.

Africa

Stanley Onyemechalu [2021, pictured right with fellow Bill Gates Sr. Prize winner Anwesha Lahiri] is a Bill Gates Sr. Prize winning archaeologist who is exploring the intersections of cultural heritage and the legacies of violent conflicts in the context of the Nigeria-Biafra war (1967-1970).

Stanley Onyemechalu [2021, pictured right with fellow Bill Gates Sr. Prize winner Anwesha Lahiri] is a Bill Gates Sr. Prize winning archaeologist who is exploring the intersections of cultural heritage and the legacies of violent conflicts in the context of the Nigeria-Biafra war (1967-1970).

He is also the Founder and Director of the Legacies of Biafra Heritage Project (LBHP), which was recognised as Runner-Up in the 2024 Cambridge’s Vice-Chancellor Awards for Research Impact and Engagement. Stanley’s research interests and publications cut across (post-)conflict heritage and memory, nationalism and separatist conflicts, critical and decolonial heritage, museums and cultural restitution, indigenous knowledge systems and public/community archaeology.

Stanley’s work focuses on the complex interaction of conflict and intangible heritage and the dissonances in memorialisation, canonisation, representation and silencing.

He says: “I argue that Archaeology in a lot of the Global North is obsessed with material things, but in places like West Africa the people place more value on non-material things such as language, food, music, festivals, dance, traditional medicine and indigenous knowledge. It is not written down, but lies in people’s memories in layered narratives.”

Stanley recently featured in the University of Cambridge’s Legacies of the Past film in which he spoke about how the Biafran War continues to shape current realities in Nigeria, especially for the Igbo people. He talked about how memories of the war are weaponised by politicians and rising pro-secessionist movements with economic and political consequences for the state. Stanley is also studying how violent conflict can have regenerative effects as well as destructive ones when it comes to cultural heritage.

Chioma Ngonadi [2015, pictured right] is an African archaeologist and a senior lecturer based at the Department of Archaeology and Heritage Studies, University of Nigeria Nsukka where she is currently the Head of Department. Her PhD research was focused on the application of archaeobotanical approaches to reconstruct the plant food production and subsistence practices among the early iron using communities in Lejja, southeastern Nigeria.

Chioma Ngonadi [2015, pictured right] is an African archaeologist and a senior lecturer based at the Department of Archaeology and Heritage Studies, University of Nigeria Nsukka where she is currently the Head of Department. Her PhD research was focused on the application of archaeobotanical approaches to reconstruct the plant food production and subsistence practices among the early iron using communities in Lejja, southeastern Nigeria.

Using multidisciplinary approaches, she combined archaeobotanical data with available archaeological information to develop a more robust approach to the understanding of long-standing agricultural practices that supported the sophisticated industrial-scale iron working technology from at least 2100 to 840 years ago.

With her experience and expertise in Archaeology of plant food production, she is committed to developing a methodology for determining archaeological parenchyma [cellular tissue] in West Africa for both wild and domesticated forms of yam and the other tuberous plants. These methodologies exist for cereal crops, which dominate the archaeological record in some parts of Africa, but not for tubers.

Alongside her research and teaching position, she had worked with the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany to translate the Adventures in Archaeological Science colouring book project into the Igbo language (one of the underrepresented languages in West Africa). In 2025, as the Head of the Department of Archaeology and Heritage Studies, she organised a special museum exhibition with the theme ‘Igbo Cultural Heritage in time Past’ in commemoration of the maiden Ofala festival of his Royal Majesty, Igwe Samuel Ikechukwu Asadu.

She has also written and published several academic articles in reputable journals, including The Archaeology of Igboland, Southeastern Nigeria and Lejja archaeological site, Southeastern Nigeria and its potential for archaeological science research among others. She has received numerous invitations to speak at various conferences in Africa and the United Kingdom.

Latin America

In Latin America, Gates Cambridge Scholars are probing a complex and often violent past to understand the present. Oscar Espinoza-Martin’s MPhil in Heritage Studies covered two main topics – the potential for decolonising heritage discourse and the political genesis of heritage.

He says: “As an Indigenous archaeologist, I am concerned about the sociolinguistic implications of applying heritage argot in academic research within Indigenous contexts. During classes, I questioned the use of cultural heritage as a legitimate category for labelling Indigenous experiences. However, I also challenged myself and considered different strategies for building bridges between ways of experiencing what we called heritage and cultural properties. Although it is complicated and challenging, I believe it is important to aim at building horizontal and culturally appropriate bridges between heritage discourse (Eurocentric, rational, Cartesian, etc) and Indigenous knowledge and ontologies.”

He says: “As an Indigenous archaeologist, I am concerned about the sociolinguistic implications of applying heritage argot in academic research within Indigenous contexts. During classes, I questioned the use of cultural heritage as a legitimate category for labelling Indigenous experiences. However, I also challenged myself and considered different strategies for building bridges between ways of experiencing what we called heritage and cultural properties. Although it is complicated and challenging, I believe it is important to aim at building horizontal and culturally appropriate bridges between heritage discourse (Eurocentric, rational, Cartesian, etc) and Indigenous knowledge and ontologies.”

Oscar [2024, pictured above left] is also interested in how archaeological heritage is shaped by fragile nation-states during wartime. His dissertation, which was awarded a distinction, examined the political histories of two UNESCO World Heritage sites in Peru (Machu Picchu and Chavín de Huántar). Both sites were inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List during Peru’s internal armed conflict (1980-2000) as part of a military strategy to counteract the actions of two non-state armed groups who were attempting to dismantle the Peruvian state.

He states: “The sites were not physically destroyed, unlike what might happen in Europe, but they were symbolically used as weapons of war to instill fear among civilians. Heritage and trauma were intertwined, representing two sides of the same coin.”

Part of his dissertation will be published in Oxford University Press’ forthcoming Handbook of Heritage and Security.

Since leaving Cambridge, Oscar is back in Peru and researching the criminalisation of Indigenous and non-Indigenous people for their participation in political manifestations in Peru (2022-2023) against the authoritarian government of Dina Boluarte.

He says: “As part of the riots, 62 Peruvian citizens were extrajudicially killed as a result of police and military actions. To grieve the losses of their loved ones, Peruvians built precarious memorial sites across the country, which are under threat from the current government. My research seeks to explore the connections between criminalisation, rooted in “racial” or “ethnic” features, and memorialisation practices under authoritarian regimes in Latin America.”

He hopes to do a PhD on this issue and to create a GIS-driven webpage to raise awareness of human rights violations in the region.

Margot Serra’s PhD in Biological Anthropology focuses on the earliest communities in coastal Peru who lived around 10,000 years ago, mapping their transition from mobile groups of fisher hunter gatherers to the more settled communities that laid the foundations for Andean civilisation.

Margot Serra’s PhD in Biological Anthropology focuses on the earliest communities in coastal Peru who lived around 10,000 years ago, mapping their transition from mobile groups of fisher hunter gatherers to the more settled communities that laid the foundations for Andean civilisation.

Her work reconstructs Middle Preceramic (ca. 7000-6000 BP) lifeways in the Lower Ica Valley of Peru, relying on a comparative osteobiographical approach that integrates archaeological, bioarchaeological and paleopathological lines of evidence.

Because of the extreme aridity of the region, much has been preserved, including organic matter such as skin and hair. That has enabled Margot [2023, pictured above right], who analyses burials in early Andean culture, to look at diet, health and mortuary patterns, combining broad patterns with osteobiographical data in order to reconstruct individuals’ lives and expand our knowledge of how early Andean communities adapted to major changes.

Sara Morrisset [2016] also conducts archaeological excavations on the Peruvian south coast. Sara, who was co-editor of The Archaeological Review from Cambridge journal, is currently focusing on the study of cultural and artistic revivals in the ancient Americas.

Sara is Assistant Professor of History at Westmont College in the US, where she teaches Latin American and world history. Her PhD in Archaeology was on memory, identity and the role of revival and traced changes in the material culture of the Ica Society on the Peruvian South Coast (c. 1000– 1600 CE).

The Pacific

Dylan Gaffney’s research investigates the crucial link in our understanding of how ancient humans initially migrated through Island Southeast Asia into the Pacific and how they adapted to thrive on small rainforested islands.

Dylan Gaffney’s research investigates the crucial link in our understanding of how ancient humans initially migrated through Island Southeast Asia into the Pacific and how they adapted to thrive on small rainforested islands.

While he was doing his PhD, Dylan [pictured left and top] told Gates Cambridge: “I want to know what enabled our species, Homo sapiens, to disperse to a wide variety of new and challenging ecological settings while the Neanderthals and other hominins stayed in more favourable habitats.”

His PhD focused on the Raja Ampat Islands, West Papua, which had not been previously excavated despite its strategic importance linking Indonesia and New Guinea, the gateway to the Pacific. After leaving Cambridge, Dylan [2017], who is from New Zealand, moved to Oxford where he has continued and expanded the field programme he developed at Cambridge, working on the earliest human dispersals out of Africa into Oceania.

A recent paper based on his PhD reports the earliest occupation of the Pacific islands over 50,000 years ago. His research team revisited some of these islands in 2023 and are now finding even earlier deposits which they are working on radiocarbon dating at Oxford.

Dylan, who is Associate Professor of Palaeolithic Archaeology at the University of Oxford as well as an Honorary Lecturer at the University of Otago in New Zealand, has developed quite a large multidisciplinary field team, with a strong emphasis on capacity building with Papuan scholars, working with ecologists to do camera trapping, anthropologists to explore local people’s conservation practices and oral histories, alongside ongoing archaeological work on cultural heritage. The blog section of his project website updates their work. His team also published two books on the archaeology of New Guinea. He says: “West New Guinea in particular is almost totally unexplored archaeologically.”

Europe

In Europe, Margaret Comer [2015, pictured right] is exploring issues related to Soviet repression. She is currently a Research Assistant on the project “Memories of Soviet Repressions in Post-Multi-Colonial Post-Soviet Spaces”, funded by Poland’s National Science Centre and based at the Institute of Ethnology and Cultural Anthropology at the University of Warsaw in Poland.

In Europe, Margaret Comer [2015, pictured right] is exploring issues related to Soviet repression. She is currently a Research Assistant on the project “Memories of Soviet Repressions in Post-Multi-Colonial Post-Soviet Spaces”, funded by Poland’s National Science Centre and based at the Institute of Ethnology and Cultural Anthropology at the University of Warsaw in Poland.

Margaret, who did her PhD in Archaeology, is researching how aspects of Soviet repression – such as mass arrests, mass shootings, mass deportations of civilians to “special settlements” and gulag camps – are “differently memorialised, musealised, heritagised”, silenced or forgotten in Estonia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Latvia, Lithuania and Poland. For example, she has recently been analysing sites of memory in Poland related to mass deportations of people from Poland as well as sites of memory in the places to which were deported in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan in order to see which themes, iconography, language and memorial tropes are shared between sites, how and why.

She asks: “How do models of “how to remember” mass repression develop in various communities, and how and why, in response to geopolitical and sociocultural shifts, do they change over time?”

In September 2025, she was invited to present a talk, “Why Do Some Pasts Refuse to Die?” as part of TedxAstana (Kazakhstan), in which she reflected on the importance of preserving Kazakhstan’s gulag heritage, not just for Kazakhstan’s sake, but for the world’s if there are any lessons to be learned from past mass repression.

Ancient snakes

Andres Alfonso-Rojas [2022, pictured left] loves snakes and his PhD in Zoology explores their evolution from ancient times. He uses fossils and molecular data to study the diversification of snakes, especially colubroids, in the Neotropics.

Andres Alfonso-Rojas [2022, pictured left] loves snakes and his PhD in Zoology explores their evolution from ancient times. He uses fossils and molecular data to study the diversification of snakes, especially colubroids, in the Neotropics.

There is a big fossil gap between Colombia’s Titanoboa, one of the largest snakes that ever existed – which dates back to around 64 million years ago when South America was an isolated land mass and is related to today’s anacondas and boa constrictors – and smaller and more diverse colubroids, the group that includes vipers, coral snakes, vine snakes, racers and many other snakes commonly found nowadays. Andrés says it is inferred that these smaller snakes came from elsewhere, probably North America. They could have swum or jumped from island to island, before the closing of the Panama isthmus, but no-one yet knows why that might have happened.

Andrés’ work involves the use of molecular phylogenies (dendrograms like family trees) and ecological traits of modern snakes, such as what prey the snakes ate and whether they lived in trees or on the ground, to reconstruct the ancestral ecology of early South American snakes. “I am trying to reconstruct what happened to the ancestors of different types of snakes using a probabilistic model linked to climate and geological events,” he says.

He has also been looking at giant snake fossils which are related to modern anacondas and recently led a study which analysed giant anaconda fossils to deduce that they reached their maximum size 12.4 million years ago and have remained giants ever since. The study was widely covered in the press.

Alfonso says: “Snakes to me are the most beautiful creatures that exist. They look so simple, but they are so complex. They can glide, swim and burrow. They are so varied. I want people to see how amazing and beautiful snakes are.”

A critical look at Archaeology

Gates Cambridge Scholars have also turned their lens on the whole process of Archaeology. While Suzanne Pilaar Birch has striven to make the discipline more inclusive of women and Oscar Espinoza-Martin and Stanley Onyemechalu are taking a decolonial approach, Madalyn Grant [2024, pictured below right] is questioning the foundations of the discipline itself, particularly in relation to repatriation issues.

She says that Archaeology is a discipline steeped in human emotions, although its practitioners tend not to confront their own feelings, preferring to foreground their professional objectivity. This tendency complicates sensitive discussions, particularly when it comes to a topic like repatriation, she argues.

She says that Archaeology is a discipline steeped in human emotions, although its practitioners tend not to confront their own feelings, preferring to foreground their professional objectivity. This tendency complicates sensitive discussions, particularly when it comes to a topic like repatriation, she argues.

“We need to better understand how we research and mobilise to all aspects of the past – however emotional, however uncomfortable – in order to have productive conversations about reconciliation, repatriation and creating institutional trust,” she states. “Understanding emotions has a critical role to play in these interdisciplinary and intercommunity conversations.”

Her PhD in Archaeology turns the microscope towards those who are involved in repatriation, about whom there is very little data. Madalyn, who was Repatriation Manager at the University of Queensland in Australia, states: “Because of a lack of data on the emotions of those who are involved in the return of Ancestral Remains, the assumption has held that Indigenous peoples are overly emotional when it comes to repatriation. Typically, Anglo practitioners – myself included – feel an obligation to pedagogies and modes of objective practice that we were taught, but these have been racialised and moralised. We need to look reflexively at these framings. I think emotions will play an important role. They rehumanise us and re-educate us. They make the field more approachable and the hard conversations more nuanced and productive.”