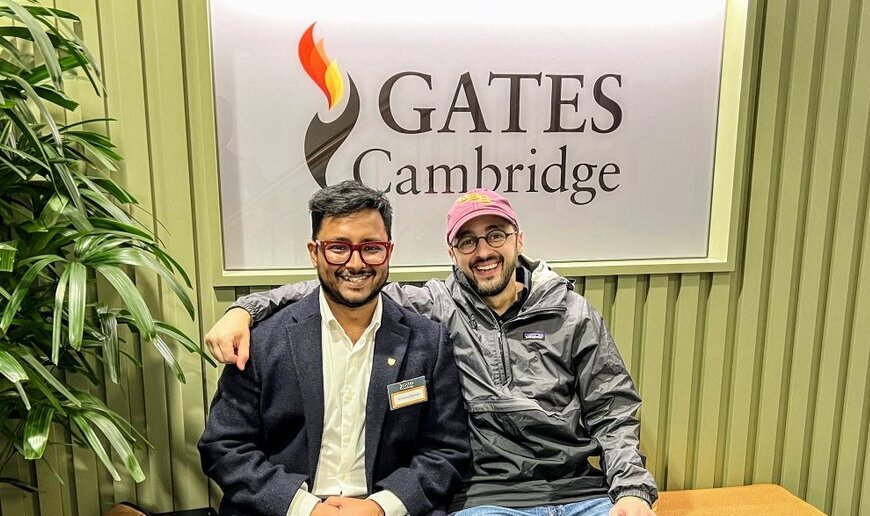

Gates Cambridge Scholars Ramit Debnath and Kamiar Mohaddes are from different cohorts and different disciplines, but are working together to tackle climate change.

Disciplinary boundaries are beginning to disappear as we focus more on the problems. And the boundaries need to be porous so we can explore new ways to address the issues.

Ramit Debnath

What do an economist and an environmental sustainability researcher have in common? Quite a lot, it turns out.

Kamiar Mohaddes [2005] is an economist, who has been working on climate economics since 2015 when he read an article talking about how rich, ‘cold’ countries might ‘benefit’ from climate change. “I found that puzzling,” he says. “How could countries like Russia and Canada benefit when there was extreme warming in the rest of the world? I started working on the pure economic and sectoral impacts of climate change.”

Ramit [2018], meanwhile, had started university life in electrical engineering then moved to Architecture for his PhD. His research explored pathways to provide affordable and accessible energy to people living in poverty in overcrowded cities of the Global South . He now leads the Cambridge Collective Intelligence & Design Group as a University Assistant Professor and was the inaugural Cambridge Zero Fellow. Much of his recent research has been on climate and AI-related topics such as modelling the health and gender impact of global heating and building defences against misinformation and misperceptions about climate change and carbon footprints.

Kamiar and Ramit met through the Energy Policy Research Group at the University of Cambridge in 2018, Ramit’s first year at Cambridge. The two met again soon after at a Gates Cambridge event in the University Centre. It was there that Ramit realised Kamiar was a Gates Cambridge Scholar. After that event, the two met up regularly to chat. Ramit said he learned about economics research from Kamiar and was impressed at how connected Kamiar was.

Ramit’s strength, meanwhile, was on the computational side and on social justice and monitoring public opinion online. The two scholars started to work together on academic papers on energy justice issues. “We wanted to provide data-driven evidence that policymakers could use to change policy and make better decisions,” says Kamiar. “It was not about getting published in top journals. It was about how we present an empirically grounded story to policymakers.”

The two had been thinking about the idea for an interdisciplinary research initiative focused on climate, nature and sustainability. However, they weren’t sure where its home might be. “We had been getting our message out through social media, but we wanted to create a community,” said Kamiar. The two had started bringing people together from different disciplines and from Anglia Ruskin for lunch every Monday to discuss their research. Then Covid happened. “The whole idea was about being in the room together,” states Kamiar. When things began opening up a little, they tried to revive the lunches, but they didn’t have much funding. Then CRASSH [the Centre for Research in the Arts, Social Sciences and Humanities] stepped in. They were setting up new labs and asked Kamiar and Ramit to apply.

A new lab

ClimaTRACES was one of three inaugural labs and officially launched in May 2024 with a focus on four key themes: Communication & Communities, Macroeconomics & Sustainability, Green & Sustainable Finance and Nature & Biodiversity. They got seed funding from CRASSH and, after launching in May 2024, were able to run a large international conference with the Judge Business School. That showed there was a lot of interest in what they were doing.

Ramit, who is a University Assistant Professor and Deputy Director of the Centre for Human-Inspired AI, says the ClimaTRACES workshops every Monday allow people from different disciplines to get feedback and to talk across disciplines. They enable people in the arts, humanities and social sciences to see the impact they can have on climate change, despite most of the funding tending to go to sciences and technology.

Kamiar, who is an Associate Professor in Economics and Policy at Cambridge Judge Business School, adds that arts, humanities and social sciences “can make a huge difference with a small amount”, given those disciplines require less investment.

Ramit says: “Disciplinary boundaries are beginning to disappear as we focus more on the problems. And the boundaries need to be porous so we can explore new ways to address the issues.”

Ramit and Kamiar have big plans for the future, including AI hackathons, hiring research students and bringing together climate design best practice in cities around the world to exchange knowledge and celebrate success. They also want to cross boundaries between researchers and undergraduate students and between the public and private sectors.

Both Ramit and Kamiar are actively looking for funding support to transform this initiative into a global centre of interdisciplinary people-centric climate research.

*An edited version of this interview appears in the Gates Cambridge 25th anniversary magazine, which is just out here.